The Way | Learn | The Whole Work of a School

Character Learning In Theory And Practice

Character learning in theory and practice must grow the whole person. We believe that our model for character education describes how an education for character might operate in any school. Individual schools may well choose to develop their own models or to tailor this particular model to suit their own contexts. Nonetheless, a model around which shared understanding and, eventually, a community of inquiry and practice might be built, is both desirable and possible. This model must show how character education occurs in every part of the school, is built through relationship, refined through specific pedagogies, and propelled by the culture of the school.

An education for 21C character and competency must be built according to design principles that encourage educators to plan, share, coach, measure, listen for, live, grow, and defend it. Through a blend of explicit and implicit, deliberate and spontaneous learning, it must seek above all to grow the whole person.

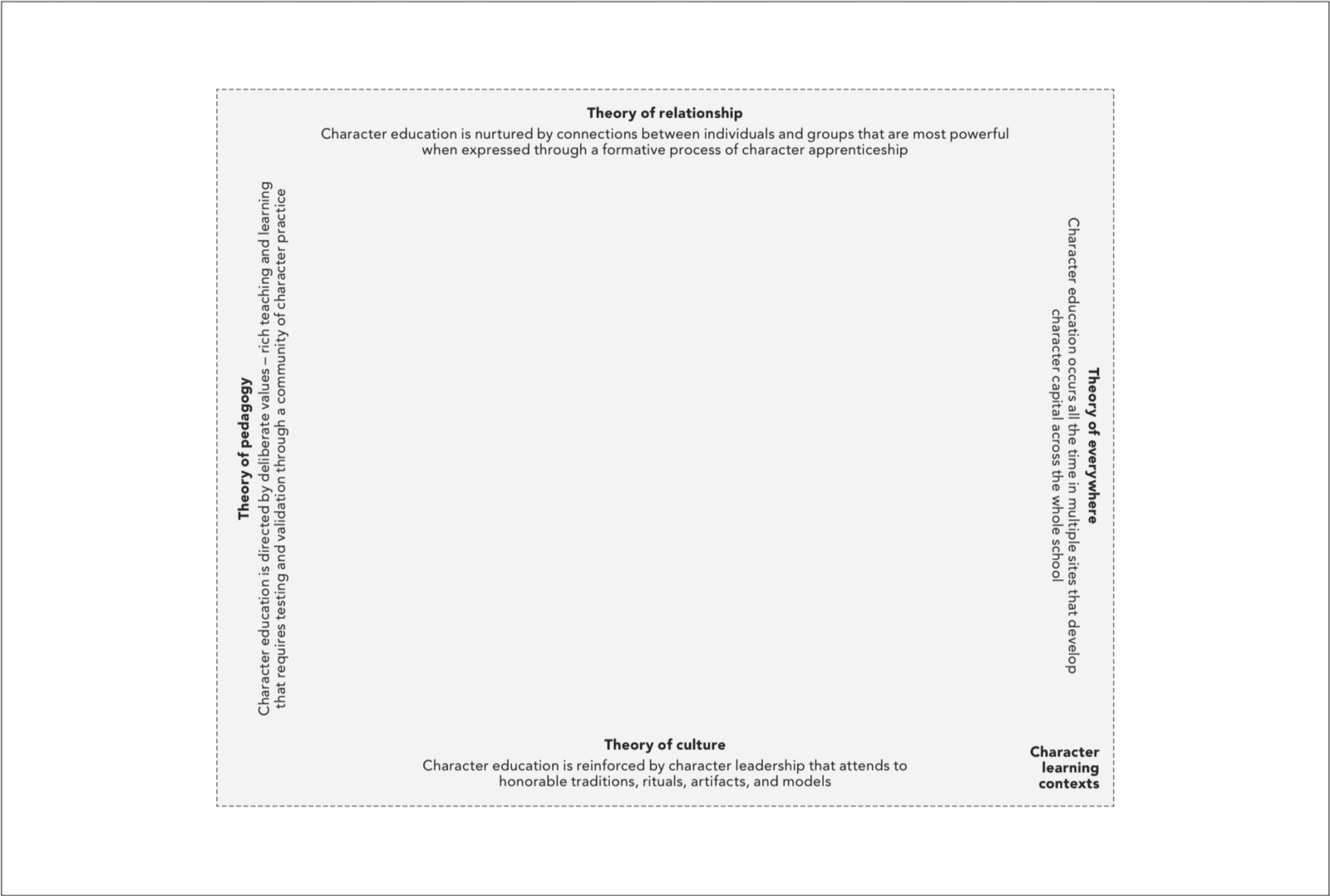

We will consider first the three domains of the experiences, design, and contexts of character learning that sit in the middle zone of our model for character education. We begin with the four critical theories we have developed to describe the influence of learning contexts for character learning, shown below:

Learning Contexts in A Model of Character Education

In the theory of relationships, we see character education being nurtured by connections between individuals and groups that are most powerful when formed through a formative process of character apprenticeship. Character apprenticeship is associated with the theory of relationship and provides the most significant medium for all teaching and learning. It points to particular relationships in which individuals go through a process of moving from being novices to experts in character competency. They, in turn, help others develop their own mastery of character. One teacher tells us that, “A boy’s relationship with his teacher is essential if the teacher has any hope in developing or influencing a boy’s character. The relationship has to be an authentic one that also takes into account this generation’s interests and realities. For example, the influence of social media on this generation is huge and as adults we need to embrace this and use it. The only certainty we know is that these boys will be facing change on a daily basis so all we can do is to equip them to deal with this alarming rate of change. For example, developing their own resilience and grit to be able to see opportunities in the challenges and to be self-motivated and driven. Once a relationship has been established with the boys, I am in a position to be heard and have a better chance of ensuring that these boys will develop into good and honourable men.“

In the theory of culture, character education is reinforced by character leadership that attends to honourable traditions, rituals, artefacts and models. Character leadership is integral to the theory of culture. It refers to the specific character labor exercised by leaders in modelling character and developing character competency, as well as reinforcing character education through the signal matters and incidents of daily life that constitutes the cultural groove of a school. Character education efficacy results from the will and capacity of leaders to embed a shared commitment to ‘what we want, why we want it and how we do it’ in character education. As one teacher says, “Being consistent in your message and finding ways to connect it with the lives of the boys is important, but finding novel ways that appeal to the nature of boys is the key. Embedding character and values education in the culture of the school has been achieved by creating characters that the boys can identify with and aspire to emulate ... The character traits and values modelled by those adults and older students silently but powerfully communicate the message.”

The theory of everywhere expresses the conviction that character education occurs all the time in multiple sites that develop character capital across the whole school. Character capital is associated with the theory of everywhere and refers to the quantum of character in a community and its relevant expressions in educational practice, apprenticeship, and leadership for this character. As one teacher explains, “Character education takes many forms. It is not one lesson that you teach in a classroom or on a field; it has to be ingrained in everything that you do. Every conversation, every class, every game must reflect key elements of honesty, respect, and responsibility. Character education is not something you teach at 9AM ... and then leave alone; it is what you do all day, every day.”

The theory of pedagogy describes how character education is directed by deliberate values-rich teaching and learning that is tested and validated through a community of character practice. This is, of course, deeply grounded in the quality of learning relationships. One teacher gives us a very poignant example of this during the IBSC project: “While I do not claim to be an expert in character education, I do know what has worked well for me with my boys. I find it very meaningful for the boys when I connect them to a current event that draws on their emotions and calls them to act on them. In 2018 when the earthquake hit Ecuador, we discussed what it must have felt like to be a seven-year-old boy or girl who lost their parents or siblings in the earthquake. The boys decided they had to do something to help. We imagined what it must feel like in the midst of the aftermath of a hurricane. What would make them feel safe and okay? The boys decided to make love dolls so the boys and girls in Ecuador could hug them and feel safe and loved. We mailed the dolls along with cards written in Spanish to Ecuador. In the meantime, I posted a photograph of the love dolls on the ‘Saving Ecuador’ Facebook specific program or place and that specific page and described what the boys had pedagogies can be identified and tested made and why. The responses on Facebook from the people in Ecuador were amazing! Over one thousand people liked our post of the love dolls and hundreds commented to share their love and appreciation to the boys. This project made a huge impression on my students that they can be agents of change and hope and love.“

Currently, many schools engage effectively with the theory of relationship and the theory of culture. All schools need to develop their practice further in these areas and also develop additional greater collective expertise in the theory of everywhere and the theory of pedagogy. This requires an initial acknowledgement that character learning is not located singularly in a specific program or place and that specific pedagogies can be identified and tested for consistency and quality of delivery of intended character outcome. This speaks to a new understanding of professionalism in the appreciation of a rigour in approach to contexts for character learning. It cannot be considered to be good enough to base an approach to teaching and learning on waiting for moments and then capitalising on them through apparently enlightened improvisation. While some good work can be done in the moment, there is much scope for intentionally refining a craft in character education that is based on what might be anticipated and tested for validity using the same sorts of evidence-based practice that has now come to be accepted in all other areas of what we do in education.

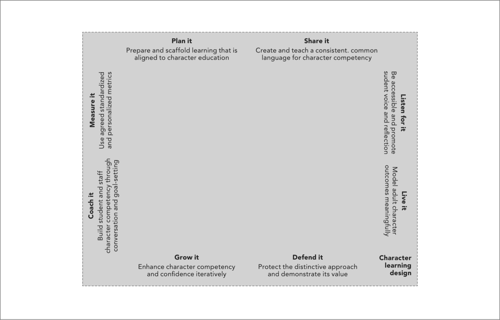

Learning Design in A Model of Character Education

“Boys are more unsure of themselves than society generally accepts. It is vital that boys learn to look at themselves, to ask themselves how they are doing, to value themselves and their own trajectory, to accept being different, to realise the full extent of their potential and capabilities – not just in academics, sports and music, but as human beings."

The next logical step from this is to consider those fundamental principles that might be derived from evidence collected across schools internationally as to how individuals and groups of teachers might design character learning. There are eight principles of learning design that our study suggests should influence the way in which learning operates within the four theories:

-

Plan it: Prepare and scaffold learning that is aligned with character education objectives.

-

Share it: Create and teach a consistent, common language for character competency.

-

Coach it: Build student and staff character competency through conversation and goal-setting.

-

Measure it: Use agreed standardised and personalised metrics.

-

Listen for it: Be accessible and promote student voice and reflection.

-

Live it: Model adult character outcomes meaningfully.

-

Grow it: Enhance character competency and confidence iteratively.

-

Defend it: Protect the distinctive approach and community of practice.

Currently, practitioners in schools feel most comfortable designing character learning around principles five to eight. One example of this approach can be seen in the following statement from a teacher: “I don’t consider myself to be an expert, but I am a teacher who believes in the value of character education. As such ... it’s extremely important for me to be consistent, honest, and continuously mindful of the character I display. If I am to help students develop the types of characteristics I want to see, I have to do my best to exhibit them honestly myself. I also believe that part of developing good character is admitting when you’ve made a mistake and taking the right steps to correct your errors. Again, modelling this behaviour is important for students to see.“ We believe that all educators need to become experts at employing all eight of these design principles. This would be best supported through development of specific professional learning programs that address these principles in communities of inquiry and practice.

This professional learning needs to be grounded in data and narratives drawn from the full range of character learning experiences within the profession. These might be most profitably discussed next.

Learning Experiences in A Model of Character Education

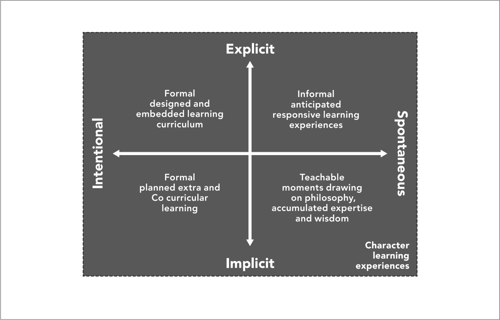

From what we have seen in our study and more broadly, we feel that the character learning experiences that are shaped by the eight learning design principles can best be situated within a quadrant formed by two axes that stretch from ‘explicit learning’ to ‘implicit learning’ and from ‘intentional learning’ to ‘spontaneous learning’. This allows us to identify four types of learning experience:

Explicit and intentional pedagogy

Formal designed and embedded learning curriculum can be seen in the deliberately constructed units of learning that consciously integrate character into the classroom and are usually the subject of formal formative and/or summative assessment programs.

Implicit and intentional pedagogy

Formal planned co-curricular and extra-curricular learning may also lead to specific deliberately planned character education. The shape of this learning is often drawn out within an experiential mode and its assessment can usually be distinguished by its performative or competitive environment rather an academic one.

Explicit and spontaneous pedagogy

Informal anticipated responsive learning experiences see teachers prepare for moments that might reasonably be anticipated in the normal course of events. These can be seen in the conversations about academic misconduct, personal integrity, the need to work hard and so on, that teachers visit with cohorts in a predictable fashion. They know they will happen and so they develop responses in advance so that when the time comes, they are ready to engage students in the matter at hand equipped with the confidence of a pre-prepared position and sometimes even resources to support them.

Implicit spontaneous pedagogy

Teachable moments drawing on philosophy and accumulated expertise and wisdom arise when teachers and students find themselves placed in a context in which matters of character arise perhaps less predictably. Teachers use their experience and accumulated wisdom to construct learning experiences ex tempore to meet the needs of the moment.

Currently, many primary or elementary educators tend to emphasise explicit pedagogies while senior school educators tend to emphasise implicit pedagogies. Most educators default to one of these approaches. We believe that all educators need to become experts in the pedagogy and curriculum of all four types of learning experience.

As one educator tells us, “Boys are more unsure of themselves than society generally accepts, and this is compounded by parental anxiety and over-protection. It is vital that boys learn to look at themselves, to ask themselves how they are doing, to value themselves and their own trajectory, to accept being different, to realise the full extent of their potential and capabilities – not just in academics, sports and music, but as human beings. It is possible for boys to go through secondary education never having given thought or time to these questions and it can lead to unhappiness or lack of fulfilment in the future. I realise that none of this is actually about my so-called expertise, but I would say that these are the principles that guide my practice.”

What comes next, therefore, is for us to build an understanding of how the model is brought to life most particularly by the educational relationships inherent in a school’s community of inquiry and practice.