The Way | Learn | The Whole Work of a School

A Model For Character Education

We need a model of character education to understand the whole work of a school. We believe that it is important to understand how, what we do individually in character education, can be situated within a model of what we do collectively. The operation of character education in a school can be best understood through a model that situates broad theory within specific learning contexts, design principles and experiences, as well as the exemplary practice that occurs in them.

Educators can usually speak with confidence about what they do within their part in the life of a school. They can observe some of what happens elsewhere. Few educators currently operate with a robust understanding of the whole ecosystem in which character education operates in a school, nor do they have an adequate model that they can use to evaluate their own practice within this whole.

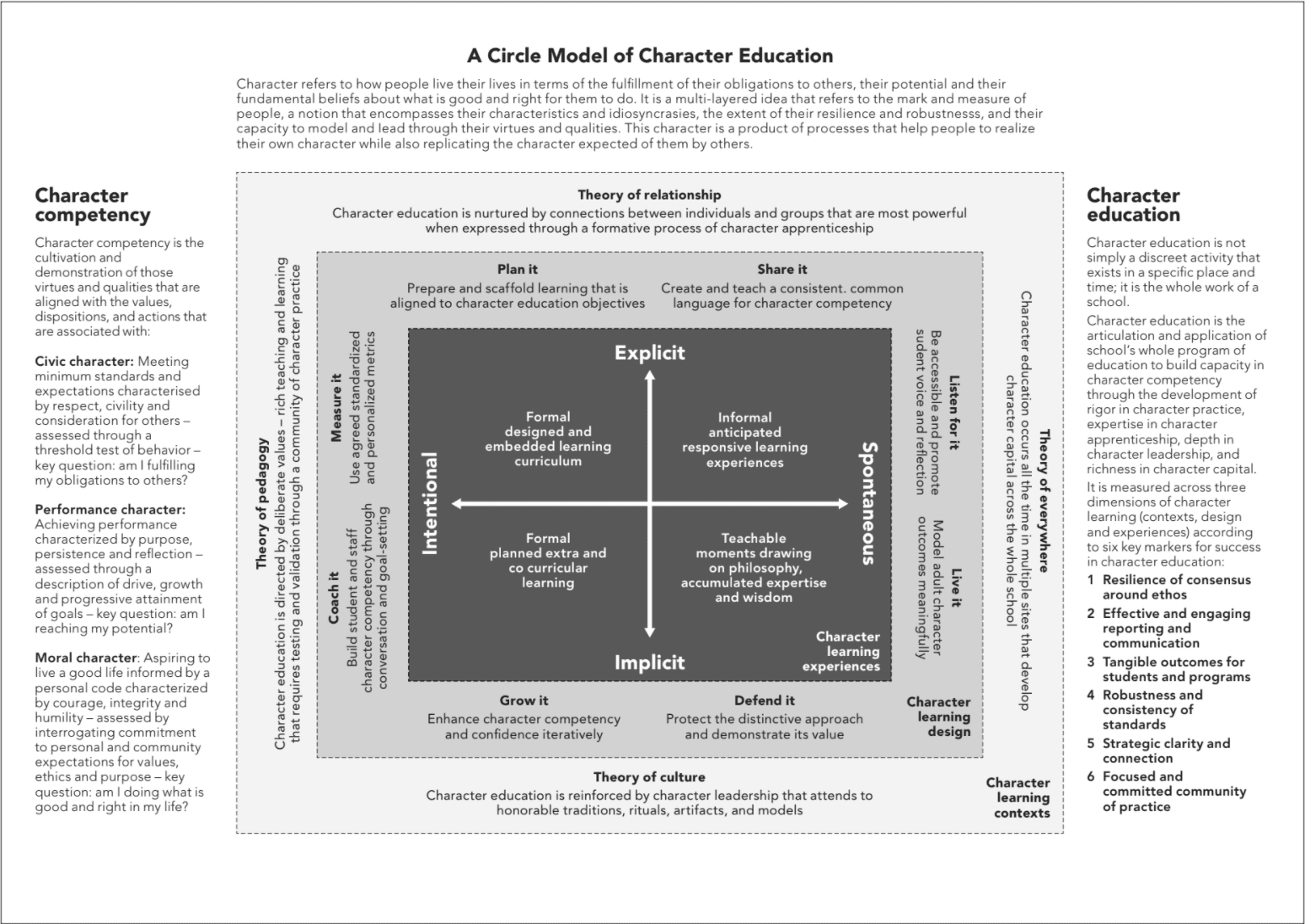

Put as simply as possible, our model of character education has four zones. Across the top is our definition of character. To the left is our definition of character competency in the three areas of civic, performance, and moral character, as well as the key questions used to inform assessment of character competency. To the right is our definition of character education and the key markers for identifying success in it. The middle zone shows the relationship between the experiences (which includes the curriculum for character learning we outlined in the previous chapter), design, and contexts for learning about character.

A CIRCLE Model of Character Education

We have spent some time looking at what we mean by character and how we might organise (at a high level) a curriculum for character learning that offers students a full range of opportunities to learn about and demonstrate good character. Let’s explore some of the other ideas on our model in greater depth.

We begin with the left zone of the model. We have already been introduced to the basic notion of character competency, but what does it look like and how might we measure it?

We suggest that we should want to measure both the process of students’ learning about character, and also the product of this learning – what they can show from their character competencies, qualities and outcomes. Technically, it is possible to map out the attainment of product goals for each of our six graduate outcomes which comprise a good person, future builder, continuous learner and ‘unlearner’, solution architect, local regional and global citizen and team creator. The qualities associated with these are comprised of integrity, complexity, growth, wisdom, perspective and connectedness. The related competencies are comprised of character, communication, change readiness, creative and critical thinking, citizenship, and collaboration.

Teachers who are too quick to judge students as failing a simple binary test of performance character or moral character run the risk of consigning students with room for growth and maturity to a category where this potential is unrecognised or rejected.

We could do what is often done in our profession which is essentially to trace a linear progression which attempts to chart a typical learning journey in a competency grading system that describes cumulative growth in capacity by pointing to what additional knowledge a learner can do at each stage. This implies a combination of knowledge, skill, disposition and reflective capacity in the fashion of the four-dimensional competency model which we have adopted.

Let us take this thinking about measurement and reflect on the nine character strengths we identified within our definition of character, comprising of three each for civic character (respect, civility, consideration for others), performance character (purpose, persistence, reflection), and moral character (courage, honesty, humility). When we looked earlier at character competency, we noted that we were particularly interested in tracking the mark and measure of people by assessing the cultivation and demonstration of those virtues and qualities that are aligned with the values, dispositions, and actions that are associated with civic, performance, and moral character. Let us now refine the definitions of these terms first offered in the introduction to this series in the following fashion for the present context:

Civic Character

Civic character focuses our attention on the fundamentals of what every person should and should not do in relation to obligations to the society of which he is a member. Typically, this involves, in the first instance, meeting minimum standards and expectations characterised by respect, civility and consideration for others. Civic character is first measured through a threshold test of behaviour informed by the key question: “Do I belong?” Critical understanding required to answer this question will involve a clear comparison of the behaviours of a student in identified criteria relative to the norms expected of all citizens. Teachers should be prepared to justify the rationale and usage of such norms.

Performance Character

Performance character helps us to see the growth in people in the execution of fundamental competencies that relate to purpose, persistence and reflection and reveal how well they function in the roles that society requires of them. People should assess the extent of their performance through a description of drive, growth, and the progressive attainment of goals in terms of both process and product, informed by the key question: “Am I reaching my potential?” Critical understanding required to answer this question will be based upon evidence and analysis of a student’s formative and summative achievement relative to baseline performance in agreed goals areas.

Moral Character

Moral character is a much more complex field that asks us to consider the extent to which people aspire to live a good life informed by a personal code that is most usually characterised by courage, integrity and humility. In terms of measurement, we can track moral development in terms of a person’s commitment to personal and community expectations for values, ethics and purpose. We can apply judgment to these individually and collectively by interrogating their integrity. This means we assess the frequency, rate, quality and consistency with which they align their values, actions and impact on the world around them according to the key question: “Am I doing what is good and right in my life?” We need to be careful of forming inappropriate judgments in this area – it is perhaps most appropriate to encourage students to reflect and make judgments about the integrity of their values, intentions, actions, and impact based on a moral code that they have, to the best of their ability, formed.

We have found in our work with schools that many educators are more comfortable with covering civic character and performance character in their daily work; some become very nervous about questions of moral character, especially when it comes to measurement as such. Many of these concerns speak to the sensitivity of teachers in the face of perceived parent backlash against a blunt but honest assessment of a student’s developing character strengths (or weaknesses). We have encouraged schools where such concerns arise to concentrate their community of inquiry and practice in the first instance (at least) on education for civic and performance character. In this case, we find that educational activity and professional interest in moral character will begin to arise naturally and lead to the development of more refined practice in how best to educate for moral character. This will also allow for the development of a nuanced conversation about how character is identified, measured, and reported in a school context.

The tangible authenticity of the following teacher’s voice gives us insight into this learning process: “I don’t know if I would suggest that I have ‘expertise’ in character education, but I do know that I (and each of my colleagues) strive to model the traits of character we emphasise with our boys. We seek to live lives of integrity at all times. I believe our boys notice the extent to which we work hard – in many different areas – on behalf of the school community’s greater good. We all multitask, and we all have tasks that our boys can probably recognise as difficult or even drudgery. I believe the vast majority of us do not complain – especially when we are with the boys – about the range of our professional responsibilities at school. I also believe we all strive to be loving and kind with all members of the community. They see us as mutually supportive in many different tangible ways – from our support of a given colleague’s ‘co-curricular’ (plays, concerts, games) to personal struggles that any of us might be experiencing.”

In addition, we find that some educators will need to review the application of their approaches to measurement of the three types of character. In particular, the application of a threshold test, while suitable for matters of civic character (which tends to be a field that is much more likely to be dominated by a discourse of rules, regulations, and codes for which a more binary or concrete way of forming judgments can be used with success more frequently) should be avoided for performance and moral character, which require more nuanced forms of measurement. Teachers who are too quick to judge students as failing a simple binary test of performance character or moral character run the risk of consigning students with room for growth and maturity to a category where this potential is unrecognised or rejected. Students resent this dismissal of their capacity to learn and improve; they will often comment adversely about being “written off” or “judged harshly” in a manner that is “unfair”. To them, this is what they see in the teacher about whom they might say, “this teacher hates me” or “this teacher doesn’t give me a chance”. While this may not necessarily be the case, it does show the damaging consequences of using the wrong type of judgment for the wrong type of circumstances. It also speaks to the power of forgiveness and the recognition that all of us make mistakes in execution for which malign intention should not be attributed automatically.