Game Changers | Learn | Teaching for Character

Assessing Character

If character is reason why we do school and is the whole work of a school, the way we assess character in a School for tomorrow. is essential. Character can be assessed through measuring progress along the growth and development of the key competencies which reveal character. These competencies can be traced through the progress that students make towards demonstrating the graduate outcomes of the school’s community.

THE SOCIAL PURPOSE OF ASSESSMENT

When we measure character, we are measuring a person’s progress along a continuum of development and performance. Progress is defined by the growth, motivation, engagement, achievement, and qualification of a person in each of their competencies. These concepts are connected intimately with each other; inherent in this connectedness is the measurement of a person’s progress according to growth in mastery of competencies, the organisation of one’s life around these competencies, and a sense of thriving in the world through these competencies. As we have seen previously, competency is the capacity to demonstrate how one has grown in character. It deliberately and simultaneously asks one to know, to do, to be, and to learn. When competency is achieved, the knowledge, skills, dispositions, and learning habits that are cultivated during the social and educational processes we experience are demonstrated in the values, actions, and the graduate outcomes students demonstrate. In short, through how students learn, live, lead, and work reveals their civic, performance and moral character.

If these are the things that matter in an education, then these are the things that we should measure. It is important that we know whether or not someone has got something “right”. But measuring the frequency, rate, quality of accuracy or coherency in a summative sense is only one aspect of assessment. Competency does not exist for its own sake; neither should individual pieces of assessment such as examinations and tests hold the power that they often do in the public and therefore our professional consciousness. Assessment is about identifying performance of a competency. This performance may serve the purpose of social selection. Thus, the passing of examinations might indicate passage into the next stage of education, including entry to into a limited number of places that might be reserved for performance of a particular quality. Yet, increasingly in a world where education is seen as a right for all, assessment must be put to some effective social purpose other than simply determining who gets in and who misses out. Numbers and rankings that have been decontextualized from the character and competencies of a person just don’t make a lot of sense in this respect.

It is in growth in character and competency as a person that we might properly locate the social purpose of assessment. If a competency asks a student deliberately and simultaneously asks one to reveal one’s character through what we want them to know, to do, to be, and to learn, then assessment must always be an opportunity to allow students to reveal this competency. Have they attained a sense of belonging? Are they fulfilling their potential, particularly in relation to the specific graduate outcomes such as good person, future builder, continuous learner and unlearner, solution architect, responsible citizen and team creator? Are they doing what is good and right in their lives? Assessment based on evidence derived from a variety of learning artefacts and the professional judgment of the teacher as to the progress a student has made in answering these questions by gaining their competencies, might ultimately serve a social purpose as stamps warranting how a student has performed in relation to their growth as a person.

Competency does not exist for its own sake; neither should individual pieces of assessment such as examinations and tests hold the power that they often do in the public and therefore our professional consciousness. Assessment is about identifying performance of a competency.

THE ASSESSMENT OF CHARACTER

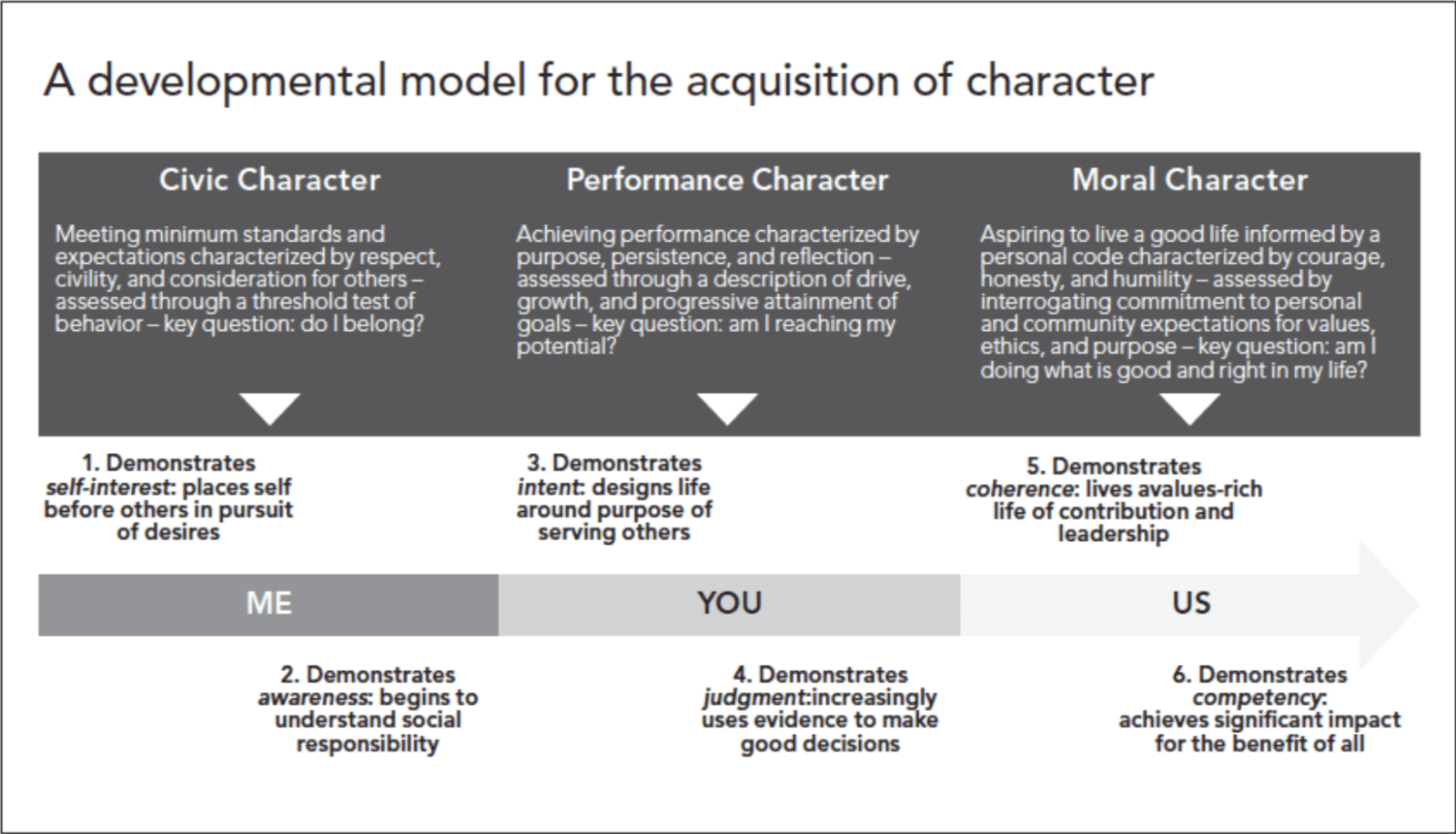

Assessment needs to acknowledge who a student is becoming, the competencies that they have gained and the qualifications that might flow from this. Assessment is, therefore, like the stamps in a passport for a lifetime of learning. It provides a process and ultimately a record of where a student has been and where a student is going. It is, therefore, less about barriers to entry and more about signifying the milestones on The Pathway to Excellence. How might we apply this more specifically to our understanding about the development and assessment of civic, performance, and moral character? As you can see from the diagram below, we can use a continuum of development from the normal self-centredness of a child to the ideal selfless of an adult to which most schools aspire to educate their students. The journey towards character from “me” to “you” to “us” is the relevant social purpose to which assessment might be put.

What we have said in terms of ‘measurement of civic character’ (or adherence to rules and principles defined for us by the community in which we live) is that we can begin by using a threshold test. If students reach an acceptable standard, then they are deemed to belong. This might suggest that if they do something often enough then they might ‘join the club’, as it were. The challenge with this is that this is what applies easily to the lesser rules – if you wear the right uniform and wear it correctly, then you’re in, so to speak. For these types of rules, we would probably veer towards defining each strength and then using a frequency scale that measures consistency of demonstration of those strengths. What happens, though, when a student breaks a big rule? What happens if, for example, the student visits significant violence on another person? Frequency of occurrence most likely will not govern the judgment of consequence under these circumstances, as if a student breaks a big enough rule then the civic code will clearly have been broken and the privileges or even membership of the group will be withdrawn, either temporarily or permanently. Thus, within civic character, we have a balance to take into account between the prevailing conditions and the measurement of compliance and transgression that apply to high-stakes rules and those rules that are deemed to be of less import. Civic character begins with meeting rules that can be easily measured through a threshold test. This compliance subsequently becomes practice centred around a deeper and richer agency in (and responsibility for) community life and obligations. With this in mind, if we wanted to construct a rubric for civic character to help teachers and students understand what is, on balance, required to meet the threshold test we have pointed to, we can look at a progression for a combination of respect, civility, and consideration for others that might look like this:

- Demonstrates self-interest: We live a self-centred life where we pursue personal gratification as our default and comply with social expectations only when these correspond to our personal desires.

- Demonstrates awareness: We develop an awareness of social norms and display a willingness to work within these rules to gain social acceptance.

- Demonstrates intent: We adopt and attempt to live through a personal code of conduct that shows our appreciation of how to balance the rights and needs of others with our own and to manage our social interactions with politeness.

- Demonstrates judgment: We align our personal code and conduct consistently with appropriate social conventions, expectations and obligations, and we show an acceptance of the need to sacrifice self-interest for mutual gain in making choices to perform our personal and collective duties to others.

- Demonstrates coherence: We exercise our responsibilities towards personal conduct and leadership diligently, and we show an increasing understanding of the reciprocal nature of living in relationship with others and how we gain mutual benefit from looking out for and supporting each other with kindness and mutual accord.

- Demonstrates competence: We influence our community for the better through our personal conduct and leadership, and we care for others freely and serve the fulfilment of their goals and needs willingly while applying and modelling the courtesies and conventions of relationship with others expected in a civil society.

We believe that we can exercise the measurement of performance character against progressive attainment of competency standards and calibrate these against the setting and attaining of goals for performance. We can describe what these strengths of purpose, persistence and reflection look like when they are exercised in both an individual and collaborative sense. In particular, in both the popular and academic literature there is an abundance of reference to concepts such as grit, resilience and drive that can sit easily within the notion of performance character (and elsewhere). We also believe that it is possible to chart a linear progression for the development of performance character through assessing disposition and the exercise of skill as follows:

- Demonstrates self-interest: We live with no clear goal or direction and act responsively and in pursuit of attractions that appear in the moment with little regard for the consequences of our actions for a preferred future.

- Demonstrates awareness: We acquire an interest in an area or a cause or a mission and begin to reject those choices available to us which conflict with this sense of mission.

- Demonstrates intent: We begin to define broad goals and strategies to achieve our mission then apply these to our daily lives.

- Demonstrates judgment: We begin to gather evidence to test how successful we are with our goals and make judgments about how well we are working towards our mission and what we might need to do to make the achievement of our mission more likely.

- Demonstrates coherence: We successfully link our goals, activity and achievement back to the cause we established for ourselves and use evidence with confidence to make fundamental decisions about whether we should continue or make changes to our course of action when necessary.

- Demonstrates competence: We consciously and consistently align our lives to our mission and use a deep understanding of the evidence available to us about what we are doing to shape the deployment our actions, energy and resources to the fulfilment of this mission.

When it comes to the measurement of moral character, many of us are troubled by the idea of grading a person’s morality. Our colleagues, internationally, (and we think we are with them on this) resist strongly, by and large, awarding grades for moral character qualities such as integrity, courage, honesty and so on. Many would argue, for example, that you can’t get a ‘B minus’ for integrity – you either have it or you don’t. Instead, we want to be able to comment on the quality of students’ interrogation of these concepts in their lives. We want to be able to identify how successfully they are able to align their values, intentions, actions, and impact. In other words, not only are we interested in integrity as a strength of character, we are also interested in the structural integrity of how what they do aligns with what they believe, and the consequences of this for themselves and others. If we pursued this approach, we might be able to assess the development of moral character accordingly:

- Demonstrates self-interest: We make choices in our lives that are situated in a sense of right and wrong that is informed by a strong sense of personal ambition and of what we believe is in our own interests.

- Demonstrates awareness: We show an appreciation of the need to forego self-gratification and personal convenience and to build a set of personal moral values that are informed by the courage to do what is right, the honesty to reflect on ourselves with candour, and the humility to understand our true situation in our world.

- Demonstrates intent: We state a commitment to living a life based on a set of principles strengthened by our desire to show courage, honesty and humility and can relate an appropriate narrative of how well and how consistently we do this in the company of others and when no one else is present.

- Demonstrates judgment: We design and implement processes to help us to evaluate how successful we are in creating tangible links between what we say and what we do to ensure that we can make a valid assessment about whether or not we are doing the right thing in our lives.

- Demonstrates coherence: We demonstrate our desire to become better people, to augment our contribution to the wellbeing of others, and to amend some of the choices we have made through brave, honest, and self-effacing self-reflection, by taking on the constructive feedback and advice of others, and by providing such feedback to others when it is our turn to do so.

- Demonstrates competence: We routinely interrogate the alignment of our values, intentions, actions, and impact on ourselves and others, and we challenge ourselves and others to become people whose lives add to the sum of our collective humanity and the good of our world.

The journey towards character from “me” to “you” to “us” is the relevant social purpose to which assessment of and for learning might be put. Each teacher needs to work through how this bigger picture plays out in terms of the more granular day to day activity of teaching and learning in school.