Game Changers | Learn | Future Schools

The Experience of Immersion Learning in Future Schools

Increasingly, schools are recognising the benefits of creating specific experiences for learning that removes students from what might be termed a “normal” or “regular” learning cycle and substitutes in a specific context that, of its very nature, challenges students to be in a space that is not what they are used to. This might be outdoor learning, excursion, exchange, service, residential, or many other versions of the same thing – an immersion that is intended to remove students from their “comfort zone”.

These student experiences are supposed to prompt new learning about themselves and their capacity, relationships, sense of belonging, and even life purpose in a social setting that requires them to look for, recognise and respond to circumstances of difference. What began with an innate sense shared by some educators that this was inherently a good thing is becoming more frequent, especially as schools are looking to establish something distinctive to establish a brand of education that helps them to stand out from the rest. This, of itself, seems rarely done simply for marketing purposes (despite the thinking of some of those who might habitually sit in cynics’ corner). The habits of evidence-based practice are slowly supplementing the predominantly anecdotal accounts of previous years. Schools are, individually, accumulating a picture of the transformative impacts that such experiences might have in shifting students further along what we might call “The Pathway to Excellence”.

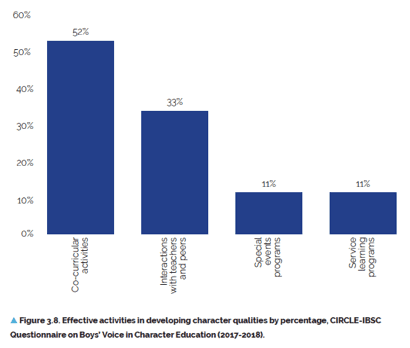

In the graphic above (extracted from CIRCLE's research study conducted for and reported out through the International Boys’ Schools Coalition in 2017-2018), we are able to see that in the minds of boys around the world, the role of learning outside the classroom is clear. When asked to name a memorable character education moment, 52% identified co-curricular events including outdoor education, 11% identified special events and programs, and 11% mentioned service learning. Overwhelmingly, students pointed to this type of learning as having an impact on their lives and the learning of character that was most significant. They also frequently describe how learning of this nature is then taken back to the other parts of their life, including the academic sphere.

The habits of evidence-based practice are slowly supplementing the predominantly anecdotal accounts of previous years.

The implications for schools from findings such as these are powerful. They speak to the value of the whole work of a school in pursuit of a whole education. Each part feeds off the learning of the other parts and, in balance and when executed in a developmentally appropriate fashion, well-designed active experiential immersion learning experiences seem to promote and cement growth in both of the cognitive and affective domains. So what does a well-designed active immersion learning experience look like?

The work of integrating theory with practice here is really only still emerging. Scholars such as Kolb, Moon, Jacobson & Ruddy have provided interesting and meaningful frameworks to help think about what an experience such as this might involve, how reflective questioning might assist it, and what the agency of the learner might be throughout the process. What is most interesting for us is how this type of theory is grounded in the practice of schools and the lived experiences of their students, and how this in turn might create a new field of grounded research findings in the area.

The Scots College, in Sydney has been working in this field now since the late 1980s. Its outdoor education campuses and six month adolescent residential programs are a hallmark of their approach, as are their other outdoor education camps, sporting activities, tours, service learning trips and so on. For them, they see active learning as the development of character, essentially experiential in nature and orientated to engagement of the mind, sense, emotions, body, and the heart in a developmentally appropriate fashion. Without engagement, boys will not learn. As a consequence, they want boys to feel connected to the place, process, participants, and product of learning, prompting a genuine sense of personal agency and voice in shaping the student’s learning experience while simultaneously stretching a boy’s capacity and strengthening his wellbeing. They are therefore not merely passive receivers of the learning experience but proactively engaged in the creation of their learning experiences. The presence of these design principles (and a variety of systems for evaluating the impact of the student and other related stakeholder experience) has gone a long way towards transforming the whole experience of learning through immersion experiences in particular. It’s been a privilege to have supported Scots College over the past decade on its journey to reinvent education – this is one such case study that we have been able to observe and to which we have sought to bring a friendly but critical external perspective.

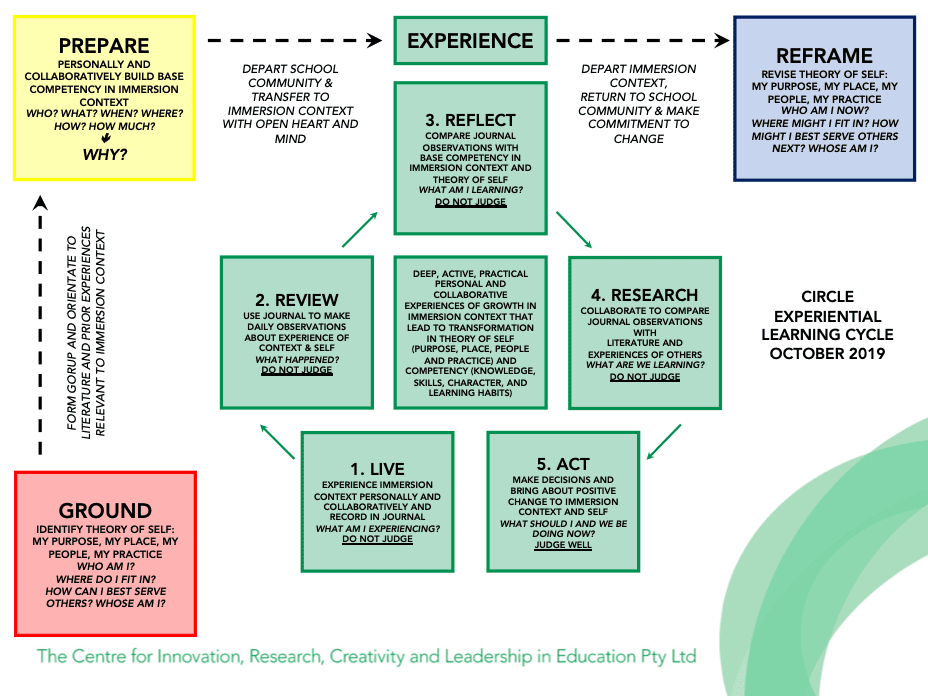

CIRCLS has also been working with the Scots team to think through the design of experiential learning in an even more granular fashion. We have shared elsewhere our model for schooling as a progression from childhood to adolescence. We wish to add to this our current thinking about how an experiential learning cycle might work within a specific active immersion learning program or event. The following diagram and brief commentary provide an overview of how this might work:

Moving from the left to the right of this cycle, we begin by grounding a learner in an understanding of themselves, prepare them to experience a context, then conduct an experience which requires them to live, review, reflect, and research, reserving judgment until it is time to act. The experience concludes with the reframing of the learner in terms of their commitment to themselves and to their community. We often talk about “saving the world, one student at a time”. This cycle can help colleagues to think meaningfully about how this might actually work. Most of us went into education to make a difference in the lives of children and to do what we could to help them to make the world a better place – this is a practical way for us to design specific learning that might actually contribute to this.

Bringing both the character-rich educational purpose of The Pathway to Excellence and the rigour of research-driven, evidence-based, and student-centred practice to the design and development of experiential learning is one key way that the learning of students is being transformed in Future Schools. We are moving from intuition and personal preference in the design of education to an insistence that what we do is based on what leading practice warrants inside and outside the classroom.