The Way | Lead | Leading for and with Character

Character Leadership In Practice

Character leadership is about how to inspire by example. We believe that currently, character leaders in schools typically have a clear picture of the daily character work and that the nature of this work should correspond to how the work of other character educators is located within their schools. Nonetheless, there seems little opportunity for them to reflect on how this work can be situated within a model or series of models that allow for the development of a cogent theory of character leadership. Such modelling at a theoretical level is essential for them to build a consistent, high quality culture of practice in character leadership throughout their school.

So clearly our research shows that school leaders tend to believe in the imperative for developing character. But how do they prefer to lead on a day-to-day basis in pursuit of this imperative?

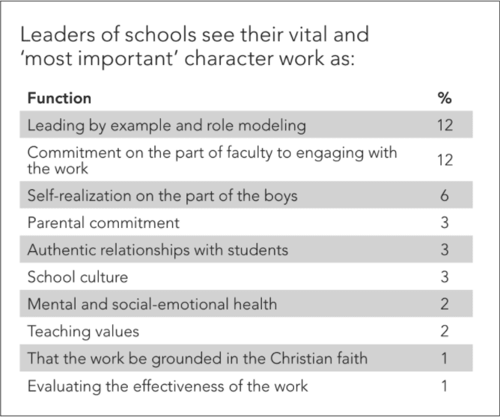

They are most strong in their desire to model character and have an impact on the students under their charge. Again and again we hear about the importance of modelling: “The most important character work is modelling, celebrating the vision and mission and modelling this on a consistent basis”, “leaders need to set a consistent but sympathetic example ... and continually reinforce the importance of good character in all aspects of life”, “the challenge for leaders is to model character”, “practice what we preach”, “the most important and vital character work for leaders in boys’ schools is modelling the qualities we ask of our boys and developing a culture within which this work can be done.”

The approach of leaders in schools towards this quest for ongoing demonstration of the way forward is, on the whole, just as intuitive, unstructured and uninformed by the theoretical models that could help them to measure their impact with greater certainty as the teachers whom they lead. One leader does acknowledge that, “For a leader for character, having an effective way to judge the success of programs is important.” Others look to key qualities to guide their efforts: “The most important character work is developing a sense of self-worth, confidence to question, and finding positive and creative solutions and engender responsibility."

In our survey of effective leadership practice within our study, we were able to draw on a wide range of rich experience in character leadership. Over 120 leaders in boys’ school contributed their thoughts as to what they did and how they did it with respect to the leadership of character in a school. Character leaders’ responses to their ‘purpose as leaders for character’ fell naturally into three groups:

Individual influencers (53%)

By far the largest group, these leaders saw themselves personally as influencing students and/or faculty through a variety of ways: role modelling; using the various forums provided by their leadership position, including addressing groups of students/faculty, discipline situations, and being members of various groups and committees; shaping programs; and in general striving to inspire and influence within or without a formal character education program. Generally, they viewed themselves as ‘relational leaders’, actively projecting their presence into the formal and informal relationships of their schools, “showing” and demonstrating what character looks like, supporting and caring for students and staff, and working with boys in their character development. The emphasis here is most often on their individual role and purpose, although no doubt solidly in alignment with other leaders. One leader explains how this works: “I think this is an important part of my role working with students as it is a major part of our school mission. I want to always show the boys that how they treat people and how they manage honour and integrity is just as important as their report card. This can show up in how I carry myself around them and set an example for the boys. It is also important from me to use verbal cues and reminders to ensure they are meeting the expectations of the school in these areas. My goal is that boys are getting better each year in these areas. Another important aspect of this work is helping teachers set good examples and lead boys effectively in these areas. If teachers are not setting the example for good character and treating others the way we would want to be treated then our actions and work with the boys are empty.”

Program leaders (26%)

This group saw the purpose of their leadership actions as aligned with and in service to an existing, formal character mission or program at their school. The emphasis of these leaders is more on their accountable delivery of and support these programs. These include leaders in faith-based schools where character work reflects and develops the values of a particular religious group through a variety of formal programs and related culture. They also include leaders in schools with formal character education programs or initiatives that are secular in nature. One leader sums up this group of educators well: “My purpose as a leader for character is to fully implement the mission of the school – which is to ‘seek truth, knowledge, and excellence; live by faith, compassion, and integrity’ – for the benefit of students, faculty, and parents. As a leader in this endeavour, it is incumbent upon me to constantly seek ways for the school to create structural opportunities for everyone to exercise these values. As such, we have created structures that ask the school community to cycle through reviews and revisions of its programs that focus on character – honour council, service learning, code of a gentleman and chapel. It is also incumbent upon me to model the attributes of the mission at all times and in all places. I need to be a vocal and visible proponent of the different aspects of character education at the school, an actor on the stage of values, not just a techie behind the scenes who makes sure the curtains open on the production of character. I also need to provide space and time for our community to stop, sit, reflect, and pursue goals directly related to the mission and thus directly related to our character-focused values.”

Cultural leaders (21%)

Leaders in this group saw their primary purpose as maintaining and enhancing a school culture that, while perhaps not having a formal character education program, had clear norms for behaviour and relationships that everyone, students and staff, understood and supported. As one leader says, “I wish to develop boys to be good people and citizens who can be role models both for their peers but for everyone that they meet inside and outside school. A concept which we constantly talk about with the boys is ‘doing the right thing’ where a sense of right and wrong is constantly engendered; so not simply doing what the rules say, but using a strong moral compass to make good choices. This breeds trust and confidence from those around you. The second area is developing individual confidence but ensuring all boys have their passions fostered and praised. All the boys are different, but the school must give multiple platforms and pedestals for them to be recognised and championed.”

It should, however, be noted that, while a leader may see her/himself foremost as an individual influencer within her/his school, it does not necessarily mean that the school does not have a formal character program, nor that it has not developed a recognised and recognisable culture that supports character development. Similarly, because a leader identifies her/himself first and foremost as being in service to a formal program or as nurturing a culture of character, it does not necessarily mean that she/he is not also performing the role of individual influencer. The key here is in how the leader identified her/his essential purpose in the her/his role. This is significant as it identifies the lens through which a particular leader sees and approaches her/his daily tasks. For many of these leaders, a sense of purpose would appear to be deeply rooted in an individual and professional ethic which they bring to their daily work. For others, an additional alignment with the mission or higher purpose of the school seems to drive and direct their sense of purpose.

In the questionnaire, leaders were also asked to state and explain the character strengths they saw as most important in the focus of their character work in their school communities. While the lists of character strengths generated in response to the second question echoes this observation, in some cases, these lists most likely replicate or significantly overlap with the stated core values of the school, in most cases the lists draw on many aspirations and formulations and are often quite specific to the individual.

Character leadership on a typical school day

The most important and vital ‘character work’ for school leaders

The biggest challenges today in educating for character

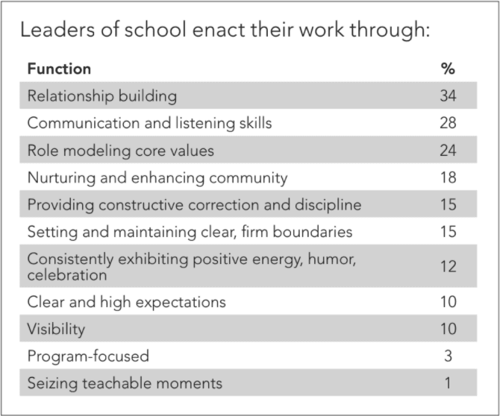

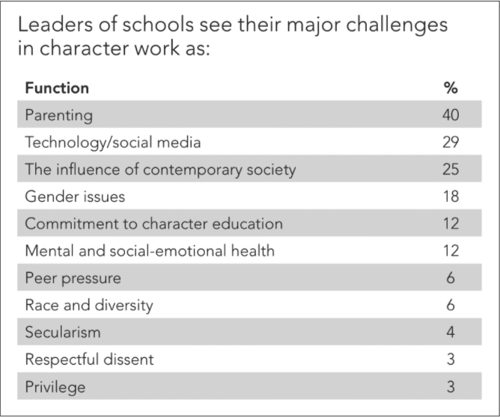

As we can see from the following charts, they conceive of their work in a fashion that largely corresponds to the prevailing culture of teaching, learning, and care in their schools; it is largely relational in nature and focuses on good communication, presence and modelling. They are dealing with a range of emerging issues that all intersect with issues that relate to the provision of an education for character, especially as they relate to social perceptions about masculinity and the proper conduct and role of people in society, as well as those that relate to the environment in which there are emerging, including parenting, technology/media.

There is perhaps no surprise in many of the challenges identified: the shift over the last generation in parenting practices; the effect of ubiquitous technology on students’ development; the influence of contemporary society’s values, or lack of, on our children, to name just the top three. Leaders unanimously testify to the fundamental importance of the work.

At the same time, character educators are posing a set of questions about the nature of masculinity in our world and the role of schools in helping their students graduate into this world appropriately. One said, “Leaders must be prepared to have honest conversations about what it means to be a man in the 21st century.” Another educator told us, “Some traditional masculine virtues may no longer be seen as positive, for example, holding in emotion. In a changing landscape of societal attitudes and standards, it can be difficult for young men to understand what is expected of them.” One directed us to think about specific qualities: “Gender identity has become a big topic of conversation. Character work that is most important for leaders [is to model] vulnerability – what it means to be a man.” Others go further still: “I think boys’ education is changing as the gender roles in society become more and more fluid and less defined. Being a boy or a man leaving school will significantly change in the next five years. One of the biggest challenges is working out what that change is and helping to educate boys as to who they are, particularly as staff are, by definition, older and often set in their stereotypes (or at least only changing slowly). There is balance to strike to create confident, strong and dynamic leaders but who are empathetic, sensitive and emotionally literate."

Others propose solutions that encourage reflection and action: “Managing bias and stereotypes in a white male dominated environment with respect to gender and sexual orientation. We must build stronger, more diverse and inclusive schools. Especially given that we are an old traditional private boys school. Empower everyone to have the courage to stand up for the values of the school and basic human rights. Call out those who violate it. Encourage accountability from everyone, boys and staff. Make the necessary changes that hinders progress and have open conversations with all stakeholders. Develop cultural intelligence throughout the school.” Again, another leader emphasised the importance of decoding “false representations of masculinity and trying to get our young men to understand that being a man has many nuanced expressions. Developing men as leaders in changing rape culture and objectification of women. How do we get young men to buy into the idea that they have the power to change the culture for women and there is a responsibility that comes with this power?”

Other aspects of what might be seen as a traditional mode of masculinity are interrogated further by our school leaders: “I believe the single largest challenge is the extent to which the broader society in which our boys live (especially for our boys, who live with a heightened level of expectation) emphasises the importance of accomplishments and achievements – in academics, athletics, and the arts. In our city, perhaps more than most, this emphasis and level of expectation always involves an undercurrent of building one’s college application resume. Because boys are given the impression that they cannot make mistakes or their dream college will become unattainable – along with the impression that their college destination has greater significance regarding their future opportunities and happiness than is appropriate – they can subordinate concerns of character in service to concerns about achievement. Because of this unfortunate environment, which if far from isolated to our community, our boys are less likely to admit mistakes, more likely to substitute integrity for a less-than-honest rationalisation of transgressions, and also manifests a reduced likelihood of acting selflessly on behalf of the greater community good."

There can be no doubt that the leaders of boys’ schools are thinking through what it means to be a man and how an education for boys should respond to this in a relevant and contemporary fashion. Traditional stereotypes are simply not accepted by our character leaders; they seek newer, better answers or at the very least, an integration of the old and the new. As one leader told us, “I also believe that honour, self-deprecation, and gentleness can be just as powerful as more traditional male ways of interacting, and also that it is important to promote a broad sense of what it is to be a male leader and role model.” On the other hand, it is surprising that only one leader mentioned the challenge of trying to assess the effectiveness of character education. The character work of these leaders is most certainly impressive and inspiring, but we sense a need and an opportunity, in many of these schools, to engage with a more comprehensive framework for character education which would provide still greater strategic and operational precision to this vital work.

Character educators clearly understand the importance of visibility in their work – they know that they need to ‘walk the talk’ of school values. As one leader believes, “People would see me, perhaps, address the school to talk about our values and specific instances where they should kick in. I would be interacting with students, parents, and teachers and reinforcing what our standards are by maintaining our character boundaries (e.g. by providing consequences for an honour violation), but also meeting with teachers to remind them of the need for compassion with a particular boy in a particularly delicate situation. I might stop by the counsellor’s office to check on a student we are concerned about. I will be questioning and confirming values while teaching an English class. I might be in a committee meeting where we discuss our outdoor education program and the need to provide opportunities for resiliency. I might visit a class to ensure that we are seeking truth and excellence in teaching and learning. I might be talking with someone about a new service program, and I might be checking with a student who needs financial assistance – to get him a pair of shoes, adjustment on his cafeteria bill, or help with a dance ticket cost.

While “visibility” appeared explicitly in some comments in connection with specific actions (supporting teachers on supervisory duty, greeting students and parents on arrival, dropping into the staff lounge), it was also implicit in the comments on building and nurturing relationships and role-modelling; it is hard to do either if one is not visible during the school day. As one leader explained, “I know the boys well. The relationship that I try to build with the boys lets them know I care for them. I try to hear them. This fosters trust. I try to model strong character, and expect the same from the boys and from my teachers. You would see me interacting with the boys. You would see in this engagement that I often direct them to integrity, scholarship and respect. I encourage boys to be nice to one another. When they are not, we generally have a discussion. I like to engage the boys in conversation rather than always telling them how to behave.” Another leader gave a similar style of response: “My verbal communication with the young men that are in my care or that I teach. I take a genuine interest in their lives, their families, and have communication with them about it – shaking hands when they have done something well, when it’s their birthday, or after general achievements or disappointments. I demonstrate a friendly mannerism with the boys where they feel that I genuinely have their best interest at heart while giving them realistic boundaries to operate, and display an attitude which highlights what I believe are the three most important values involving me and the young men that I come across – relationships, relationships, and relationships.” This speaks strongly to the same type of relational gestures that we saw earlier coming out in the character education practice of expert teachers.

Therefore, we posit that visibility is a more significant behaviour for respondents than the raw numbers might indicate. Several people addressed this in terms of scheduling meetings, dealing with email and other low visibility tasks outside of the main school day so that they are free to spend the school day “managing by walking around”. In fact, the visibility and presence of a leader for character seem to function as a foundational principle running through all of these responses. Similarly, while only one respondent specifically referenced “seizing the teachable moment”, it emerged implicitly in, or could be read into, many of the narratives. One leader explained the need of “high expectations in the classroom. Students need to be honest and act with integrity in their interactions with each other and with me, and praise and positive reinforcement in situations in which values have been displayed positively. Conversely, discussion about better future responses and decision-making in situations where behaviour and decision-making have not been guided by appropriate values.” Another leader put it: “Modelling kind and considerate behaviour to all boys ... a good use of humour to soften moments ... take punishment in a positive manner ... I look for teachable moments … I work to overcome my own prejudices and biases and encourage others to do the same.”

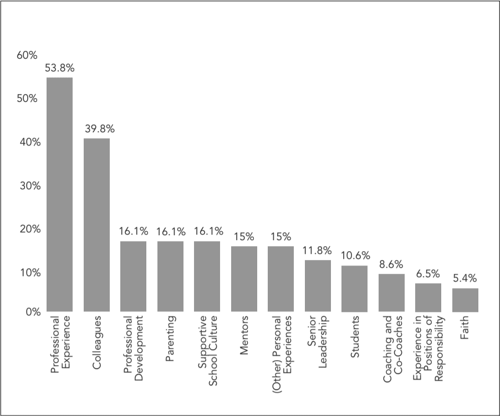

Expert practitioners see that the influence of their own colleagues, school leaders or the experience of leadership itself is critical in their formation as a practitioner. Forms of character apprenticeship are as important in the development of character educators and leaders as they are in the development of the boys themselves.

Interestingly, a significant number of character leaders chose not to mention their own actions and interactions, and instead spoke of what a ‘shadower’ would notice about the warmth and character of the school community, evidenced through the behaviours and values of boys and staff. One leader asserted that, “Most visitors comment on what a welcoming place [our school] is – visitors are frequently stopped by both students and adults and are greeted with a ‘Hello, how can I help you?’ There are students out playing on our lawns. There is a sense of community that most visitors pick up on. Visitors would witness meaningful conversations between adults and students. They would notice a sense of respect that people have for one another.” A second leader tells a story as follows: “The moment the guest arrived on campus, I am confident he or she would be greeted by many from our youngest to our faculty, asking if the person needed help or directions. There is a positive energy and spirit in the halls and in the classrooms. Boys are learning, laughing, problem-solving, and collaborating throughout the day. You will see arms around each other as there is a sense of family here and boys need and should show affection. You will hear friendly chatter back in forth and at times a healthy debate. The boys enjoy sharing their ideas, defending their positions, and learning a new perspective. You will see boys helping each other, helping teachers, holding doors, picking up trash, promoting various events from sports to the arts. Twenty-three years ago, I saw all of that and more and it is the reason I have stayed.” A third example of this is more analytical: “Visible evidence of the values in action through the way people greet each other and visitors, interact, move about the campus, enter rooms; teachers and students working collaboratively, respectfully in and out of the classroom; explicit attention to the values in assembly addresses, publications, displays; strategy meetings that use the values as reference points for decision-making; student leaders role-modelling the values; the framing of difficult conversations in the context of the school’s values; students who can reflect on their behaviour through a values lens; a happy, vibrant community that is the sum total of its intentional focus on values; a strong culture of learning in the classroom – students persisting with their studies.”

Again, an implicit leadership behaviour here might be summarised as nurturing a strong and healthy school culture. Part of this involves the demonstration of and exhortation for high standards. One leader explains: “I think our school’s effectiveness in character leadership is rooted in a shared responsibility in that critical mission. I believe that someone shadowing me – or any of my colleagues – would notice our interactions with students and the extent to which educating our boys with regard to character has no boundary. We address concerns of character in the classroom, in athletic practices, in the hallways, in our individual meetings with our advisees, or any other venue in which we interact with the boys (individually or in groups). We expect our boys to behave to a certain standard, and we expect our boys to treat others (both peers and adults) with integrity and with respect. Our interactions include constructive criticism when necessary but also plenty of praise and recognition regarding actions and behaviour we deem laudable.” Another leader added, “My demands for plain-speaking, setting of clear goals with staff and boys, demonstration of accountability – of me to others and them to me, efforts to bring out the qualities inherent in every staff member and boy, desire to temper justice with mercy wherever possible, refusal to let boys waste their chances and the gentle prodding of the reluctant into situations which will enrich their character.”

And so, the list of behaviours that emerges may be viewed as a repertoire or ‘toolkit’ for effective leadership for character, as observable in the daily work of experienced, successful practitioners. One leader sums up this practical approach quite neatly: “Approachability, organisation, goals (short and long term) clearly identified along with action plans to meet these targets; post-it notes on walls indicating priorities and planning; many people visiting my office throughout the day for work and personal conversations; a willingness for staff to assist me in projects outside their normal duties; collaboration with team members; interacting with many people during the day; being seen.” Another speaks to the importance of humility: “I do a lot of listening and collaborating. I listen to teachers, parents, and students, and I collaborate with them to make our school environment a better place. I don’t think that I have all of the answers, and I am open to the ideas of others. There are some in my role who believe that they are the smartest person in the room. The minute you fall prey to that thinking you are sunk, and great ideas that others have never get a chance to take root.” Yet another sums up the role of relationality: “Eye contact, face to face interactions, genuine interest in and knowledge of the lives and interests of our boys, clear expectations and communication, accountability leavened with good humour and understanding, flexibility, encouragement of student initiatives and a willingness to both listen and pitch in.”

How do leaders learn these tools? What is clear from the following graph is that expert practitioners see that the influence of their own colleagues, school leaders or the experience of leadership itself is critical in their formation as a practitioner. Forms of character apprenticeship are as important in the development of character educators and leaders as they are in the development of the boys themselves:

Becoming better at character education: professional influences and support