The Way | Learn | The Purpose of Teachers

The Rationales For Character Education

A great school has many rationales for character education. We believe that a healthy school community should encourage a full range of views on the purpose of an education for good character so as to reflect more closely the diversity of views held in the societies that these schools serve. Preparing students to be fit for purpose in 21C requires the capacity to see, understand, and harness multiple perspectives. Schools, by their nature, which are too singular in outlook promote a type of thinking that seems to be of less relevance to the world to be inhabited by their students. Open-mindedness and a capacity to recognise what others see and feel are qualities that need to be embedded in any school that seeks to prepare students to thrive in their world.

This influence of this issue of the breadth of perspective within the dispositions of educators (especially in relation to ongoing questions of terminology, definition, and purpose in character education) became even more relevant when we began to refine our research approach by expanding its application to interrogate in depth the objectives of expert practitioners in character education.

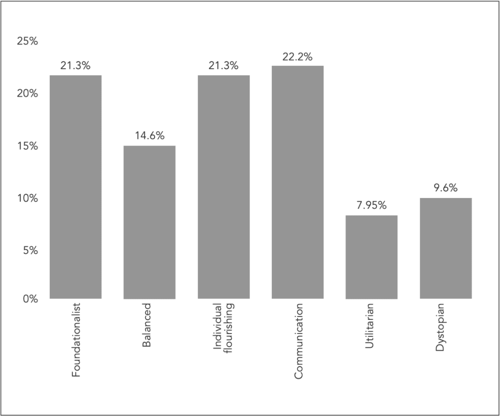

When we asked the boys’ schools participating in our IBSC study to identify their expert practitioners in character education, we were provided with a corpus of some hundreds of teachers to draw on that helped us to look at (in the first instance) this question of disposition further. We discovered that it was possible to group them into six areas of responses to the following question:

"Please provide a statement of your philosophy as an educator for character. Why do you believe that character education is an important part of your work with boys in your school, and what do you seek to achieve?"

Teachers engaged readily with the question, and many found it unusual and animating to be asked to articulate such a private and inner worldview seldom discussed in routine professional discussion. Data analysis revealed a number of clear philosophical approaches and key themes in the practices of the teachers who responded. Responses clustered into six philosophical approaches that can be seen below.

Philosophies of character education: guiding rationales of expert teachers

Communitarians

‘Communitarians’ were interested mostly in promoting character strengths that the functioning of society as a whole, particularly through a focus on producing good citizens and civic obligation. Teachers who show evidence of this approach to character education stress the importance of developing boys to become strong citizens and to seek their highest purpose in service to others in their communities. As one teacher argues, “Our most important job is to prepare out students to be good citizens ... History will affirm that no one is more dangerous than an intelligent, clever person without virtue. Similarly, much of what is great in the world will have resulted from individuals emboldened to do the right thing and to make a difference.” Others could point to the role of school culture in this respect: “Our school’s mission is to prepare boys for service. Bright and talented boys who leave our school without a critical foundation of character are not prepared or equipped for a true commitment to service.” Others still noted the importance of relationships in developing character: “By being present and involved with each boy in all aspects of his schooling, one builds a relationship of trust. Once that is established, guiding and moulding the student into an adult who will be a better citizen and contribute more positively to society should be achievable.”

Balanced

‘Balanced’ responses saw character education as a counterweight to an exclusively academic focus. Teachers in this grouping state that while different and with different claims on learning priorities, traditional academics and character education are equal in importance and should be mutually reinforcing. As one teacher stated, “The high quality of education I seek to achieve tries to encompass all dimensions of the person: academic, but also human and spiritual because all of these dimensions are connected.” Values are seen as very important in the views of these teachers. “While it is important to fill our students’ heads with valuable information, a full heart is just as important, if not more, than knowledge,” said one, while another understood their priorities as follows: “I want my students to leave my class more knowledgeable and better equipped to pursue their studies, but I also want them to leave my class as better people.”

Foundationalists

‘Foundationalists’ saw the building of character as the most important role of education, the bedrock of the entire teaching endeavour. These teachers expressed the belief that character is fundamental for boys to learn and thrive. It is foundational in the sense that it is the ground upon which everything is else is built and sustained. Some of these statements may well reflect the religious mission of the school in which some teachers worked, but a wider range of perspectives converge in this category. One teacher said, “Character education is the only thing of importance that we do. The boys here are talented, gifted, ambitious and aspirational; they will be successful academically and in activities almost in spite of our efforts and presence. Not to be almost exclusively dialled in to the character piece is to do a huge disservice to their talents, to their abilities and to their potential.” In a similar vein, another said, “Character is everything and is an underlying part of all that we do as educators.” For some, this influenced how they saw the whole work of the school: “Character education should be ingrained and integrated in all aspects of education, regardless of the specific curriculum content or subject matter.” In particular, it gives a scope and sequence to all learning at school: “The formation of character is the first target we have to achieve with the students, and from here the academic formation.”

Individual Flourishing

‘Individual flourishing’ responses focused most on building the character strengths required for providing students with the skills and competencies for well-being and flourishing. These teachers believe that character education is foremost about supporting boys to become their “best selves”; each boy is unique and has his own talents and potential. Challenging and helping boys to find their future as full human beings is the purpose of character education. For many teachers in this category, there is no prescribed model, formula, or set of attitudes and skills to direct him toward. One staff member expressed it in terms of mission: “My role is to facilitate and challenge boys to grow and learn about themselves, their physical and emotional environments and to respect each other’s right to do the same.” For another, this could be put into a religious context: “In my experience, the best environment for this type of teaching and learning to occur is one which promotes, models and celebrates behaviours consistent with Christian values. These values reflect the life and teachings of Jesus Christ as a servant leader, pointing to a life which has at its core a commitment to enrich the life, learning and experience of others.” Another still brought out the concept of making a difference in the lives of students as follows: “If the purpose of education is to make our young people into the best versions of themselves, give them a chance to find their passion, show them the opportunities that are available to them, and help them become productive members of society ... every time you speak to a student is a chance to make a difference in their day.”

Utilitarians

‘Utilitarians’ believed that character education should provide students with the urgent skills and competencies and attitudes that translate directly into academic success, focus and ambition. Teachers identified with this pragmatic approach stated that they emphasise those specific character traits that would provide boys with the tools and skills that will contribute to success in their current and future education and in the workforce. One teacher expressed it as fundamental for lifelong success: “Character building by teachers should focus on developing these core strengths (motivation, resilience and successful cooperative working). They will ultimately result in a better atmosphere in class, higher grades, and prepare students for higher education and work.” Another could place it within a very specific socio-economic context: “I am hoping to transform the lives of underprivileged students ... I want to give these students a chance to succeed inside and outside of the classroom.” Others saw their purpose expressed in a personal code that they wanted to pass on to their students: “As an educator and coach, I emphasise the importance of having good character as one of the byproducts of the five pillars of athletic, personal and professional success. Those pillars are: hard work, teamwork, sacrifice, commitment, and perseverance.” Some were quite traditional in how they looked at this type of code: “My day-to-day focus ... is on the basics: discipline, manners and relationships.” Others were more contemporary in their wording: “In today’s ever-changing environment, we must be aware that there is a strong need to develop young men who have the soft skills to enable them to succeed in the 21st century.”

Dystopians

Finally, ‘Dystopians’ believed that the purpose and function of character education was to prepare students to survive in a difficult, unpredictable and even harsh world and advocated for the need for schools and teachers to vigorously respond to the decay of social, moral and parental values. These teachers speak first to the importance of providing boys with a moral compass and the skills that will support them in resisting the pervasive, negative influence of contemporary culture and media, some dimensions of which may be particularly pernicious for boys. These responses were intense and heartfelt in their formulation. “I have always thought that education is a tool to help young people navigate an increasingly challenging world, a world in which they are victims to the insidious and false messages of a culture that only values them as consumers,” as one teacher said, while another looked to a very sharp critique of masculine discourse: “The moral fabric of society has been eroded by the lack of moral education in schools ... I believe that character education is important in any school but especially in boys’ schools. Men in our society have been for far too long the aggressors, and that can be seen in our crime statistics: abuse, rape, armed robbery and other violent crimes.”

Others pointed to broader trends in the world: “The world has changed. The dynamics of the family have changed. Our students grow up with working parents, fast-paced technology, less family time, more structured activities, and in many cases underdeveloped skills to deploy in adulthood.”

The challenge of complexity is perhaps not as easy a solution as something more uniform in nature, but that is, perhaps, the character of leadership in our schools.

In noting these six different philosophical positions, there is no suggestion of ranking or preference. We would, however, highlight the diversity of positions in which teachers from these schools work, each of which provide a strong rationale for their clear commitment to their work on character education in that school and would appear to drive their practice. It is also the case that echoes, strong or weak, of more than one approach can be heard in any one reflection, and that the boundaries between the categories can be quite flexible. In some cases, a teacher’s response bridged two or more categories and a judgment was made about the primary emphasis. Furthermore, it became clear that the focus of the particular school influences philosophy. For example, in a school with a population overwhelmingly composed of underprivileged children, a dominant approach emphasising skills and attitudes promoting academic success makes excellent sense. We also believe that if we could bring all of these teachers together for a conversation, we would find much more common ground than fundamental differences of approach.

The findings from this aspect of the research convinced us that a broad and inclusive approach to defining the nature of character and possible rationales for an education based on character was essential. If this spread of disposition were to be articulated across entire school faculties (or indeed whole communities), we would most likely see that any overly narrow or singular definition would result in disagreement from at least three quarters of the group. In addition, for the development of an holistic approach across the school, one would need to adopt an approach that allowed all staff to buy into it from the point of their original disposition, even if work in the area in time shifted their disposition to one of the other categories.

The challenge of complexity is perhaps not as easy a solution as something more uniform in nature, but that is, perhaps, the character of leadership in our schools. We look at that in greater depth elsewhere, but suffice to say now that schools need the breadth of thinking that reflects the society from which they are drawn and to which they contribute. School leaders who attempt to impose too narrow a school brand run the risk of significant alienation from their community and disaffection from their faculty, neither of which bodes well for the success of such leadership.