The Way | Work | Becoming a School of Character

A Good School And A Great School

A good school gets the fundamentals right; a great school functions as an authentic, mature, and high performing community of inquiry and practice. We believe, therefore, that a great school should track, gather evidence about, and evaluate its organisational maturity as a fit for purpose school of character. It should conduct this measurement of its high performance both in terms of the learning experiences and graduate outcomes of its students, as well as in its operation as a learning organisation.

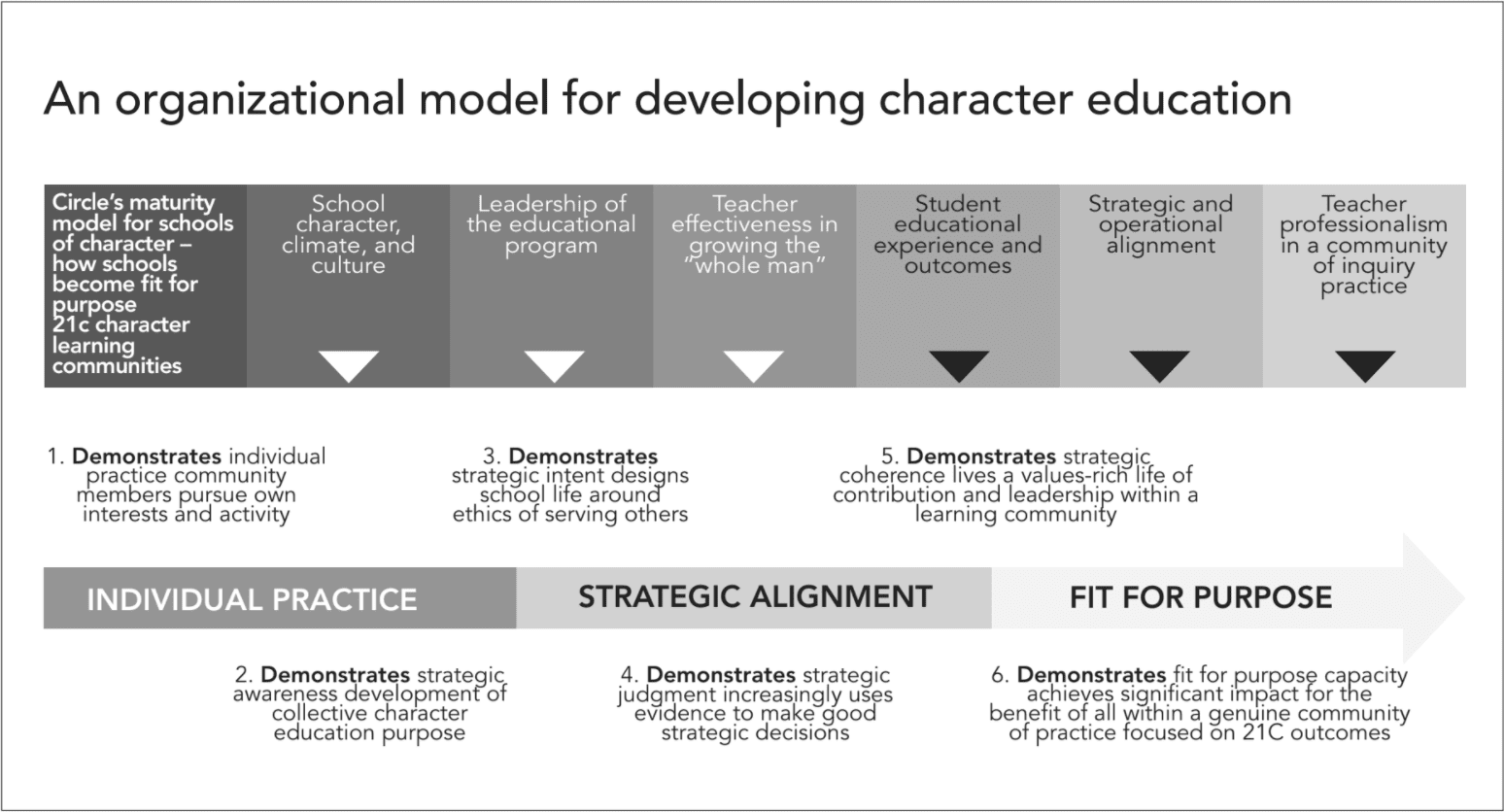

To do this, it should interrogate a set of key factors in our six corridors of an excellent 21C education that point to the character, climate and culture of the school, leadership of the educational programs, the effectiveness of teachers in growing the ‘whole person’, the effectiveness of student educational experiences and outcomes, the alignment of strategy and operations with respect to character education, and the nature of teacher professionalism in a community of practice dedicated to the attainment of its desired graduate outcomes based on 21C civic, performance, and moral character competencies. In other words, a school of character is one that consistently demonstrates an increasing propensity towards inspiring, challenging, and supporting students to fulfil their potential to be young people of character and competency.

Becoming a good school starts with paying attention to the fundamentals. A good school becomes fit for purpose by building high standards across all aspects of school life and embedding and sustaining these standards within the habits and routines of its daily life, all of which emanate from its desired graduate outcomes based on 21C civic, performance and moral character competencies. As one school leader explains, “We need young people who can identify problems and solutions that will make the world better, safer and more equitable for all. My role then is to inspire faculty to teach more than skills and content but context, to create opportunities for students to rise to the occasion and show the best of their nature.

”Fit for purpose 21C learning culture means stepping forward into a preferred future where:

- Vision and vocabulary for learning are shared

- Value proposition is agreed by stakeholders

- Velocity, shape, and trajectory of change is designed and implemented to meet the needs of internal and external contexts

We have formed the view that schools who wish to be schools of character (those schools whose deep work in educating for the character and competency of their students means that they are fit for 21C purpose), should adopt three trajectories in their strategic educational development work. The three trajectories of strategic educational development are as follows:

Schools of character should examine character education in depth

These schools place character and competency at the core of the work of education – it is seen as the essential preparation for global citizenship in a 21C context, not as an additional thing to be done. Effective solutions in this area are not off-the-shelf or pre-packaged but focus on solutions that both build on the work of others and also take into account a school’s unique context. As we saw in earlier in this book, schools of character need to develop an evidence-based approach to describing and implementing both a framework for character education and an ongoing conversation within their communities about how best to ensure the practice of a school is world-class in its approach. One school leader explains how this might be done: “Leading for character is about building a culture where positive values are modelled, and where as many opportunities as possible are provided for young people to practice and build their character. Culture begins with a language of shared values, but this cannot be where the process ends – stating we are a growth mindset school or a school which builds resilience only becomes authentic when teachers truly model and promote these character attributes and behaviours, both in themselves and in their pupils. There is also a fine balance required between the explicit and implicit promotion of character education opportunities; ideally the building of character should be embedded in activities which are valued in their own right, as is generally the case with collaborative opportunities where boys develop their individual, team and social skills over time.”

Schools of character should be thorough about educating for character

A strategic and intentional approach towards character education is more successful than reliance on assumptions about what might be happening in classrooms and other learning environments. The accidental and incidental ‘caught, not taught’ approach fails to provide high quality education for character to all students. A school of character will want to work towards systematic formal and informal means of character education for each student, implementing a range of both proven and innovative collective, collaborative and personalised strategies that are regularly evaluated for their quality and effectiveness. An aspect of this can be seen in the following perspective offered by one school leader: “My most important responsibility is to create and articulate a clear values-driven frame of reference for everyone in the organisation – pupils, parents, staff – to work within. This was derived from historic understanding of the school but updated for the present. This gives us a moral compass and provides a clear set of principles against which any decision (by any of the individuals or groups in the school) should be made. It’s really a statement of ‘our way of being’ ... which provides a path for people to follow. In carrying out my day-to-day role, I aim to exemplify the values which we would like everyone to follow (although this is often easier said than done). It is also my role to encourage others around me to do the same and, on occasion, to explain to them that they have fallen short (and why that matters).”

Schools of character should measure what they do

This is based on a belief that character can be described and changes in student outcomes in these areas can be both tracked and measured in a variety of qualitative and quantitative ways. The impact of education for character can also be measured, allowing the school to know where there is good value in exerting its efforts and resources. A school of character should develop systems that help it to replace assertion based on anecdote with knowledge based on evidence in the discourse of every member of the community when it comes to character education especially. One example of this intentional approach can be seen in the following account of a school leader: “Character development has been a foundation of our school since long before I arrived. More recently, we benchmarked ten character traits that we hope to instil in our boys. Our boys understanding of this focus on character has allowed us to develop better relationships with them. They feel comfortable in our environment and are therefore more open to absorbing what it is we are striving for. My overall goal is to mould boys with strong moral compasses. In getting boys to know and understand right from wrong, it is my hope that they apply this to all situations. Our motto is, ‘We are judged by our deeds’. I use this phrase with our boys on a regular basis. If they keep in mind that what they do and say is attended to by others, and therefore matters, they should be able use this understanding as a guiding principle of why it is they should act accordingly.”

A whole education should be personalised to the needs of individual learners and shaped with a deep understanding of the requirements of our society for graduates who will flourish in the world of tomorrow. This whole education should be driven by the knowledge engine of a community of inquiry and practice.

Becoming a great school starts with assembling the ingredients of a high- performance culture. A great school, a school of character, identifies the ‘secret sauce’ of aspirations, a sense of kinship, and pathways to success, and applies this to a culture of inspiration, challenge, and support. This culture fosters both the pursuit of excellence by young people of character, and the sense of belonging to and engagement in school. It keeps them in their groove and holds them to the educational purpose of desired graduate outcomes based on 21C civic, performance, and moral character competencies. In order to be able to ‘bottle’ the ‘secret sauce’ of a great school on an ongoing basis, the community of inquiry and practice that the school develops must understand clearly the standards of practice towards which it must aim, and the questions it must ask at the core of its habits of inquiry.

The essential element of this is the nature of inquiry that infuses each of these standards with an ongoing scholarly rigour in pursuit of educational excellence. We can, therefore, parse out in the following paragraphs the scope and sequence of inquiry through the six standards we saw in earlier in this book that can help us to see how clearly how a school community might best function and whether or not that ‘secret sauce’ of high performance is working its magic.

Resilience of consensus around ethos: We agree on what matters to us. We reinforce the resilience of the consensus about shared values, intentions and principles that enable the community to withstand the challenges of conflicting goals and hidden assumptions about educational design and delivery. Without resilient consensus, the community may be constantly challenged by conflicting goals and hidden assumptions.

- Is there evidence of strong, positive leadership, empowering governance, and supportive executive and operational structures and systems that will help the school develop and implement a shared articulation and understanding of its goals through a framework for character education?

- Is the school prepared to adopt an agreed approach to the development of valid measures of character education?

- How effectively is the school engaging its stakeholders in building consensus around the aims and practices of character education?

Effective and engaging communication and reporting: We talk about and report on our work effectively. We ensure desired school culture and strategy are aligned and translated into daily operations and community engagement through effective communication and reporting. We need to ensure operations of character education are communicated and translated into the daily teaching and learning.

- How successful is the school in preparing for the planning, organisation and consistent delivery of character education within the learning programs of the school?

- How effective is the school at identifying and articulating in a more explicit fashion the application of character to the achievement and development of the students?

- How well is the school engaging with the wider community as to the intentions, nature and implementation of its approach to character education?

Robustness and consistency of standards: We define and improve our standards. We strengthen the robustness and consistency of school standards by setting expectations, providing support, monitoring progress, recognising success, and encouraging accountability.

- Does the school understand where it has areas of success in character education and how these might be cultivated for further growth?

- Does the school recognise where there are domains in character education that require further attention and the strategies required to attain improved outcomes in these areas?

- Are there processes in place to assist with rigorous and routine monitoring and evaluation of the implementation of the school’s expectations for character education?

Tangible outcomes for students and programs: We achieve those outcomes that people expect of us. We establish and achieve both process and product outcomes for students and programs that are appropriate to both the context of the learning environment and the deliberate and targeted focus of learning, particularly in the areas of student care and character, learning culture across the curriculum and co-curriculum, student leadership culture, design and delivery of student programs and pathways, the promotion of student voice, diversity, and identity, and innovation and future readiness.

Outcomes for students: We establish outcomes appropriate to the situation and to the focus for learning.

- Does the school have a clear set of graduate outcomes that is driving its philosophy and practices of character education?

- How effectively is the school tracking, assessing and reporting out on the character development of its students?

- How well does the school draw on, appreciate and celebrate a diverse range of character education narratives from its student and alumni population?

Outcomes for programs: Academic and other departments must assert the importance of character education in the curriculum and pedagogy.

- To what extent is the school integrating character education within all fields of learning and systems for care and support of students?

- Is there a whole-school total pedagogy of character education that unifies practice in this area?

- How successful are those specific programs and initiatives that the school is using to highlight its objectives for character education?

Strategic clarity and connection: We are clear about our vision and what we do is aligned with this vision. We reinforce strategic clarity and connection in school activity by promoting intentional, aspirational and practical values that provide concrete direction for the school.

- Is character education aligned with the nature of the stated values, educational philosophy and desired outcomes for both the school and its students?

- Do staff clearly communicate and model the core stated values of the school in the work of character education?

- Do students clearly communicate and model the core stated values of the school in the practice of character education, especially in the interactions of older students with younger students?

Focused and committed community of inquiry and practice: We recognise that character education is an explicit domain of professional practice and can take place in formal curriculum as well as informally in activities. We are working together to improve what we do in character education, especially for our students. We prioritise the establishment and continuous refinement of processes, systems and structures that nurture a school-wide community of practice that unlocks defensive default positions and supports individual and collective improvement in formal and informal learning culture and practice.

- Do faculties and other staff teams understand how to approach the incorporation of student outcomes related to character appropriately into their learning experiences?

- How successful is the school in helping staff to align the practices of character education with the school’s strategic intentions for the development of the students?

- To what extent does the strategic implementation of character education include a deliberate and incrementally staged process to build the capacity of the teaching staff to adopt a contemporary approach to promoting learning in this area?

Progress in each of these standards can be individually measured according to the consistency and quality of delivery. School stakeholders should bring additional rigour to this process. They should be invited to rate and comment on these areas, which can help to gain data on which to base judgments about the nature of the educational experience and its contributing factors within the six corridors.

Altogether, however, a global and summative judgment should also be made to assist a school to concentrate its attention most keenly on doing those things that really count towards growing its organisational maturity as a fit for purpose 21C community of practice in character education. To do this, we need first to think about and assess a school’s overall capacity in character education by tracking its trajectories of student learning experience. At the same time, we must focus keenly on the graduate outcomes and the character and competencies of the students that they exhibit in keeping with these outcomes. Thirdly, we need to reflect on the whole education through which the potential of students to achieve these outcomes is optimised.

This whole education should be personalised to the needs of individual learners and shaped with a deep understanding of the requirements of our society for graduates who will flourish in the world of tomorrow. This whole education should be driven by the knowledge engine of a community of inquiry and practice. This community should be moving its faculty away from the habits of teacher sole practice within siloed departments and activities that pursue what they perceive is in the best interest of the students without necessary regard for the strategic direction of the school. They should encourage collective inquiry and aligned activity that helps to realise the school’s educational purpose and associated strategy. It should also share in and model an agreed growth mindset that sharpens the consistency and quality of what it does through the rigour of transparent, collaborative, evidence-based practice. With these qualities in place, it might begin to see itself as a mature learning organisation capable of high performance in improving outcomes for more learners.

To calibrate the judgment of the consistency and quality of this organisational maturity and high performance, we can use a conceptual model that mirrors that which we used earlier in this book to consider the development of character in individual students. In that instance, we used the underlying assumption that schools aspired towards a culture of servant leadership in which students placed the interests of others before themselves in contributing to and leading their communities. In other words, children grow into their mature adulthood when they put aside a primary interest in serving themselves in pursuit of service of the needs of others. Likewise, great schools serve their communities.

The maturity of the school’s capacity to articulate and achieve its strategic intentions for an education for 21C character and competency within its deliberate, targeted and intentional models and educational frameworks can therefore be tracked along a continuum that examines the progress of its learning culture from individual practice to strategic alignment to being fit for purpose in serving the society in which it operates:

- Demonstrates individual practice: We permit community members to pursue their own interests and activity in character education with little authentic connection to each other’s practice beyond a base level of compliance to regulatory or broad community expectations.

- Demonstrates strategic awareness: We begin to compare practice and develop a collective sense of our shared and individual purposes in character education.

- Demonstrates strategic intent: We draw on our understanding of our community to design school life and the character education that occurs within it around an ethos of serving others.

- Demonstrates strategic judgment: We increasingly use evidence, particularly of the six strategic markers (resilience of consensus around ethos, effective and engaging communication and reporting, robustness and consistency of standards, tangible outcomes for students and programs, strategic clarity and connection, focused and committed community of practice) to make good strategic decisions about how best to pursue, recognise, and celebrate character education goals and strategies.

- Demonstrates strategic coherence: We can demonstrate consistency and quality of character education that allows many in our community to live a values-rich life of contribution and leadership within a learning community.

- Demonstrates fit for purpose capacity: We achieve significant impact for the benefit of all within a genuine community of inquiry and practice focused on 21C outcomes that prepare our students especially to thrive in the world of tomorrow.

Measuring the Organisational Maturity of Schools of Character: From Individual Practice to Strategic Alignment to Fit for Purpose

Measuring the Organisational Maturity of Schools of Character: From Individual Practice to Strategic Alignment to Fit for Purpose