The Way | Work | The Character Work

The Call To Character

It was an atypical English midsummer day. The sun was shining, and London was reeling from that strange type of heat that feels like it's in the high 90s, when it's only in the low 70s on the Fahrenheit scale. The educators gathered at the City of London School in July of 2011 had just been treated to a highly entertaining speech by an English politician who had ridden onto the stage on a push-bike. He delivered a rapid-fire collation of opinions, bon mots, witticisms, and provocations about the role of values and character, amongst other things (including the importance of the classics), in boys' education. You can guess what his job might be now...

As the attendees moved onto the luncheon area to chat amongst themselves, we lingered in the foyer over some mediocre coffee and started musing over what we had just heard. Brad Adams was at that stage the Executive Director of the International Boys' Schools Coalition, a collection of hundreds of schools for boys from all over the world who gathered together regularly in a community of practice and discourse to investigate and advocate for the best outcomes in boys' education. Phil Cummins had recently acquired Creative School Management, a leading educational consulting firm based in Australia. He was beginning to re-establish it as CIRCLE – The Centre for Innovation, Research, Creativity and Leadership in Education. Brad and Phil have continued their collaboration together through a School for tomorrow.

CIRCLE is now the research institute for a School for tomorrow. We are passionate about helping schools develop the organisational, professional and personal competencies to align their performance with the needs of the new social contract for education: today's learning for tomorrow's world. We do this because of our unwavering commitment to improving outcomes for more learners. Since 2010, CIRCLE has worked with hundreds of schools (and school organisations like the IBSC) to build excellence in leadership and learning cultures that equip more students with the character and competencies needed to thrive in their world. In doing so, we seek to assist schools in becoming evidence-based communities of inquiry and practice focused on educating future-fit citizens. We do this in multi-year, longitudinal partnerships that involve a combination of research, development, and management consulting in education, supported by an extensive network of like-minded schools and their educators.

The conversation Brad and Phil had on that day in July 2011 homed in on the concept of character that the earlier speaker raised. Character education, a topic of great interest in the United States from the 1980s onwards, had been a matter of particular interest for schools worldwide for at least a decade or so. We agreed that many schools took it for granted that they did add character to their students and lauded their merits accordingly in their publications, prospectuses, websites, and other promotional materials. Yet, in Brad's words, "How would they know?"

At that time, there was a clear gap in the understanding at the 'chalkface' about what education is and how its impact might be measured in the value-added to the education of the students. We began to explore the opportunity a little further, teasing out how this gap might be filled before the events of the day took over.

Building a Global Network for An Education For Character

Over the following year, Phil began to think this through further, bouncing ideas off Brad. The latter created space in the next annual IBSC gathering program in Richmond, Virginia, where a group of schools emerged from a well-attended workshop and proposed an investigation into the measurement of character education outcomes. This initial study was formalised in 2016 into a large-scale two-year research project sponsored by the IBSC and 49 participating schools. It involved thousands and thousands of stakeholders – teachers, leaders, parents, and (most importantly) students.

In the background to this specific work in character education, our work in developing a synthesis of much of the leading literature on contemporary learning culture led us to refine our existing theory of domains and criteria of school improvement into a sharper knowledge architecture. At roughly the same time, out of the small group of IBSC schools who demonstrated interest in this work from 2012 onwards, emerged in 2015-2016. A group of schools internationally wished to enter into a partnership with CIRCLE to take part in what some have come to call a "deep dive" longitudinal research-driven work in how best to frame an education for character within the specific context of their communities. This involvement gave us a unique opportunity to add to our understanding a series of intimate portraits of communities from the perspectives of families and practitioners.

Our study for the IBSC, Character Education in Schools for Boys, was designed to investigate and report effective practices in boys' character education. The project explicitly aimed to propose a well-researched framework for schools to evaluate current practices, processes, and programs in character education; to sharpen strategy and planning for character education; to develop meaningful and authentic outcomes; to create standards for accountability, reporting, and professional learning; and to communicate this focus and consensus to the broader school community. This framework for character education was intended to be respectful of individual school culture and tradition and thus serve boys' schools better than prescriptive models espoused by specialist organisations and agencies in character education. We have learned from our work with boys' schools internationally that the framework might encompass both a theoretical approach to the content and methodology of an education for character, as well as a pragmatic process whereby ideas are captured, shared, refined and embedded within the guiding documents and practice of a school.

Two further large-scale research opportunities arose contemporaneously. The Association of Boys' Schools of New Zealand had already conducted some significant research into the outcomes attained by boys in boys' schools. While they knew that boys in boys' schools outperformed boys in other schools across all benchmarks, they wanted to know why this occurred. Similarly, the South African Boys' Schools were deeply connected with the original work with the IBSC and wanted to learn more about building our standards for excellence and work in character education.

Two ongoing projects commencing in New Zealand in 2017 and South Africa in 2018 respectively drew on thousands of responses involving teachers, leaders, parents, and boys from across the whole sector of boys' schools in New Zealand and South Africa. The work was intended to significantly deepen and broaden our understanding of building a framework for boys' education excellence. This was done by generating substantially more data at a global level to develop and articulate this framework and to document best practices in boys' schools across New Zealand and South Africa. The context of boys' education provides a unique lens by which these standards of educational excellence might be framed and examined, particularly in six key areas by which the culture of a great boys' school might be assessed in-depth: student care and character; learning culture across the curriculum and co-curriculum; student leadership culture; design and delivery of student programs and pathways; the promotion of student voices, diversity and identity; innovation and future-readiness.

At the same time, from the heart of the range of our work beyond these two projects, we saw that the future belongs not to any single-gender but people of character more generally. In our eyes, this refers to people equipped with a particular set of competencies with which they graduate school ready to succeed in a world that expects a great deal from them, perhaps more than any generation before them and without any clear road-map of how to fulfil these expectations.

Calling Schools to The Character Work GloballySchools that systematically go about doing the right things in the right sequence and use evidence to support the efficacy and efficiency of what they do are much more likely to lay down a proper platform for enduring success in character education.

We discovered over the past decade the building blocks of graduate competencies that could help our young people to thrive in their world: good people of integrity; future builders who can negotiate complexity; continuous learners and unlearners who grow throughout their lives; solutions architects who provide direction for us all; responsible citizens with a local, regional and global perspective; and team creators imbued with the relationality to bring people together with all of this in mind.

We found that schools often lacked the cohesion and clarity of purpose required to optimise all students' schooling experience and set them up for a life of ongoing meaningful work, learning, contribution, and fulfilment. We saw that without a clear picture of the articulation, integration, and synthesis of a set of graduate outcomes linked to character education goals that are the proper object of the collective labour of a school. Let us prelude our understanding of these competencies by considering how we help students explore learning through the experience of their school education. This might seem somewhat lofty or abstract in tone, but it quickly becomes very hands-on when we look at what we do when we teach and when students learn.

In generations past, many young educators were taught by colleagues in a fashion that seemed to serve their curriculum well. They separated the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes specified in our curriculum and taught them discretely. In less enlightened educational settings, it may have been common for students to experience a week where we might, for example, do knowledge on Mondays through Wednesdays, skills on a Thursday, and testing of attainment on a Friday. A windy afternoon brought disruptive challenges to this structure, but such things in a school always seem to get in the way of a well-intentioned plan. Values and attitudes were much less concrete than knowledge and skills. Many of us were somewhat nervous about approaching this seemingly more nebulous area; we were reluctant to impose our values explicitly on the students, even while we did our utmost through our modelling and methodology to do so implicitly. What students believed and the related character that they formed was the unspoken and frequently hidden curriculum.

While we may have achieved some good public examination results by drilling and skilling in knowledge, our ability to help students form a whole picture of their learning, their world, and ultimately their place in it was most likely hampered by our approach. This was because then (as now), students do not live in a body and use a mind that compartmentalises these things – they form whole ideas and try to apply them to live an entire life. Our humanity is complex and defies our attempts to simplify or streamline it, no matter how much pressure we are under to present the two-minute pitch or summarise it all in a page with a few dot points.

Helping students build an economic analysis of History, for example, without contemplation of the moral dimension of education, is very dangerous. It encourages a view that we can and should objectify History (or any other discipline) dispassionately in the pursuit of a morally unacceptable end. We can allow ourselves to take the humanity out of the story of people and dissect the parts of our story with an almost macabre and certainly dispassionate coldness. We can lose the relevance in pursuit of the rigour which, as Bill Daggett and the Model Schools movement based in the International Center for Leadership in Education would remind us, results in further alienation of students from the learning process and further isolation of schools from the societies in which they exist. We need both rigour and relevance in our lives, and thus we need both in our education. If character, as we have come to believe, is the actual work of future-fit schools, then we need to ensure that we have grounded our practice in character education that is both rigorous and relevant.

We need to recognise and educate students both for and in step with the holistic nature of the character and competencies that most effectively express the best of humanity in our times. Therefore, our approach is informed by theoretical and practical understandings that a quarter of a century of much improved educational research and thinking has brought us. We no longer try to split what we do into discrete components; we understand that education is a values-rich environment that must be shaped and explained to have both integrity and quality for all learners.

Forming a Multi-Dimensional Framework For Character Education

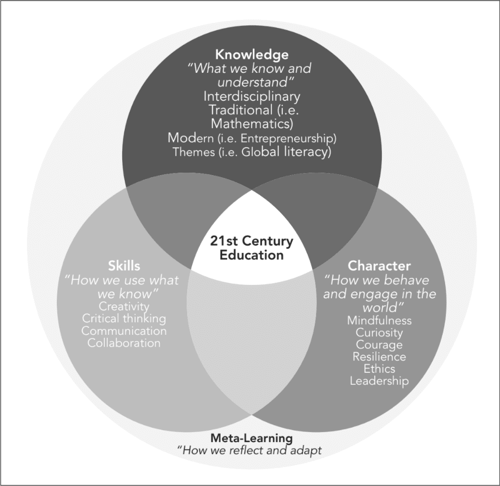

Our thinking internationally is being shaped by models that ask us to contemplate how we integrate the essential knowledge, skills, character, and learning habits required by school graduates into everything we do. This means that the work of character is so often about building this type of holistic competency. In practical terms, in any given lesson, rehearsal, training session or the like, we cannot teach the knowledge without the skills, we cannot pretend that we are not forming character, and we know that we must incorporate reflection on this overall process if we are to optimise learning.

Recent models for future-fit education propose an intersection of complex educational purposes within an integrated everyday learning practice of every teacher and every student's experience. However, the challenge of expressing the holism of an education for character is best demonstrated, we believe, by the Center for Curriculum Redesign's four-dimensional model for education. This model for learning is rapidly acquiring significance for educators and educational systems worldwide today in their thinking about the aims, purpose and practice of education. Since 2016, it has proposed a four-dimensional model for education that now sits at the core of what we believe is most relevant in the best thinking about character education.

Four-Dimensional 21st Century Education, Center for Curriculum Redesign (2016)

This four-dimensional model calls on us to approach education, specifically education for character, differently from the more diffused modernist mode we referred to above. It puts knowledge, skills and character together while overlaying meta-competencies related to reflection, understanding of the process, adaptation, and growth (which themselves might frame within the competency of change readiness).

Students learn, what they know, can do, and are disposed towards are drawn from the four-dimensional model of education advocated by the Center for Curriculum Redesign. Thus, we believe that the process of educating for character is expressed best through a set of graduate outcomes and develops through holistic competencies. These graduate outcomes and their enabling competencies can be articulated in a framework that can shape the educational enterprise and align it to the essential work of a school – the character of its students.

In other words, the 'rush to agency' where people seek to enact change that addresses and improves the practice of teachers or the outcomes of the students without first undergoing the reflective work of looking into and identifying the whole character of a school and its approach to character education is unwise. From what we have seen, it is more likely to lead to initiatives that might look efficient and even effective on the surface but fail to improve meaningful educational outcomes for more learners. On the other hand, schools that systematically do the right things in the correct sequence and use evidence to support the efficacy and efficiency are much more likely to lay down a proper platform for enduring success in character education.

We believe that within a school, the call to character is best answered through the expression of a framework for education. We believe that the best starting point for embedding the desired culture of a school of character within everything that it is and does should be this notion of a framework for education. This set of essential educational documents should be based on guiding questions and concepts that integrate the knowledge, skills, character, and learning habits required for authentic future-fit education. Therefore, character should be broken into a series of specific competencies and overarching meta-competencies that should influence, inform and instruct the whole learning activity.

In seeking to embed such a framework of thinking behind contemporary and future education for our young people, schools should first seek to create the leadership and governance that both understand and nurture the challenge of constructing a compelling narrative that links yesterday to today to tomorrow. This can position them to build systems and processes that develop the capability of people to derive educational solutions based on predicted future needs for the education of our children. Only then will they be best placed to address the learning at the 'chalkface' and, therefore, build cultures of excellence in learning in communities of inquiry and practice that balance evidence with wisdom in creating better character education.