The Way | Live | The Power of Relationship

Professionalism In The Teacher Community Of Inquiry And Practice

The teacher community of inquiry and practice works best when directed towards collaborative professionalism.

We believe that teachers currently reveal themselves to be strong character educators in the following four ways:

- Character educators are reflective. Expert teachers think deeply about their vocation as educators for character and are able to articulate their purpose and approach. They are also able to identify the core character strengths and values they seek to nurture in their students. These are most often specific to individual teacher, and they show a range of robust engagement with what matters in the character development of their students. These teachers recognise that character education happens all the time, anywhere and all the time across their professional responsibilities and multiple presences in the school.

- Character educators are relational. They most often refer to their relational connection to students as the richest pathway for their impact as educators for character. They are able to describe how this relationship-building, while an end in itself, is always used to engage them in their character development. They stress the importance of this relational connectedness – deploying a range of relational gestures, role modelling positive character traits, and being and being seen as authentic. This relational connectedness is not vague and mysterious; these teachers see it as a practical skill. So much of this involves a high degree of situational judgment.

- Character educators are organised. They are able to identify, describe and evaluate specific practices for pedagogy, curriculum design and classroom management that they considered to be especially effective for student character growth. They see shaping the culture of their classroom – routines and norms of the everyday teaching environment – as impactful. They are able to identify many forms of assessment, especially in the realm of informal and formative assessment, that could be used to provide feedback. Very few think that learning in character educational cannot be measured or evaluated in authentic and appropriate ways but most are not yet confident in how to do this.

- Character educators are sole-practitioners. Generally speaking, these teachers have become good at character education by reflection on their own maturing practice and teaching, and through the influence of other exemplary colleagues and leaders. A minority draw on the ethos of the school, on the explicit programs, or the strategic emphasis on character education. For some teachers in some of these schools, these are powerful. In its current state in schools, there is a hidden and tacit world of professional expertise in character education that needs to be made explicit. There needs to be an organised and evidence-based community of inquiry practice at the centre of character education.

What about expert practice in character education? There is a seamless and holistic quality to the practices or approaches narrated in the accounts we have read from teachers all over the world. The character education objective is more commonly woven through the activities, approach and content of character learning in an organic fashion. Often, however, it can be harder to unearth specific, intentional, designed, and measurable learning exercises in the work of educators.

Character education is seldom abstracted from learning as an external imposition or object of study. It most often emerges in situated learning in the classroom or in any school program, area of operation. Situated learning lends, in one way or another, a sense of urgency or purpose, an authenticity in the relationship or action, and opportunities. Situated learning can be structured or be in the nature or rule-boundedness of an activity, and at its best presents a challenge or struggle or problem of some sort.

We are always impressed by the reflective disposition of expert character educators, and by their willingness to apply their reflection to what is for many a less comfortable or secured area of practice. To be sure, a minority will say or agree that character education is a less defined and describable area of practice. But most are able to articulate and to watch themselves doing something, and to pick apart aspects or dimensions of their practice.

There is a seamless and holistic quality to the practices or approaches narrated in the accounts we have read from teachers all over the world. The character education objective is more commonly woven through the activities, approach and content of character learning in an organic fashion. Often, however, it can be harder to unearth specific, intentional, designed, and measurable learning exercises in the work of educators.

Teachers integrate their work on character education organically into their overall work in the school, whether in the classroom, in the gym, arena, or on the playing field, on the stage, in pastoral groups and all the other forums within which to engage the students. Although it was sometimes the case that they reported working collaboratively on design of a common lesson or unit, or were part of a larger program initiative, the majority of these teachers told us that they worked in relative isolation.

As indicated, overwhelmingly expert teachers in the boys’ schools studied in the IBSC research project considered that relational strategies and relational presence seemed to be the most powerful conductor for engaging boys and opening up opportunities for their impact as educators for character. They seem certain to say that forging such relationships builds, in the words of one teacher, “relational capital” with boys and their parents, to be spent or used in difficult situations. Some said that building relationships leads to a better understanding and a greater appreciation of boys; this contributes to framing situations differently and with less confrontation, for example. Perhaps most importantly, they seem to report that boys are more attentive and focused, and readier to trust and engage, when there is a strong, respectful relationship with the teacher and when they feel that they are known and valued. Others emphasised the importance of “role modelling” positive values and expectations, noting that the boys are constantly observing and evaluating their teachers, and that they are always alert to the “character messages” their actions transmit. A third group focused more specifically on the authenticity of these relationships and this role-modelling, and the effectiveness in letting boys see vulnerability and humaneness.

Another group of teachers speak to the importance for boys of having lessons that are current and relevant, “exploratory”, “active”, “hands-on”, and give them opportunities to “encounter the world”, find out “where they fit”, and “how and where they find purpose”. These activities invite them into exploration and discovery about the issues and challenges and provide “room to discover who they are”. “Authentic outcomes” seems especially powerful and significant when the objectives are specifically in the realm of character education.

Yet another group of teachers emphasise the power of high and consistent standards and expectations for boys as a telegrapher of character strengths. These could be high standards for achievement, effort, or behaviour, challenging students and showing that the teacher believes that they have the potential and capabilities to meet the challenge. Teachers further explained that standards and expectations need to be fair and consistently applied, and that there needed to be “clear, frequent, honest and timely feedback”. Boys, they said, respond positively to such high standards if they believe that their teachers believe in them, and that the whole process of holding them to high challenge and standards needs to be based in relationships based on trust and support. Others wrote about the need for boundaries on the part of students and the need to enforce these consistently.

Some expert character educators also argue that boys in particular are often not naturally communicative and therefore need opportunities and encouragement to speak reflectively and personally, and that they need guidance to find a vocabulary for their feelings and more complex thoughts. Activities and interactions that invite boys to practice and develop these interpersonal and reflective skills in a supportive and caring learning environment are especially generative of social-emotional and relational learning.

One thing that interested us was that relatively few teachers directly acknowledged the value of boys holding up ideals of manhood – heroes from history and literature, the ideal of the southern gentleman, military personnel, sportsmen, and religious figures such as Jesus. It is perhaps worthy of note, and gives pause for thought, that this does not come up more frequently as a theme, given its pervasiveness in the literature on masculinity and the influence of role models. The power of sport as a vehicle for character development is not also dominant in the accounts of teachers. It is again of note that the positive impact of competition and teamwork, with the right kind of character leadership, does not come up more often, especially because of the common assertion that boys are naturally absorbed by sports.

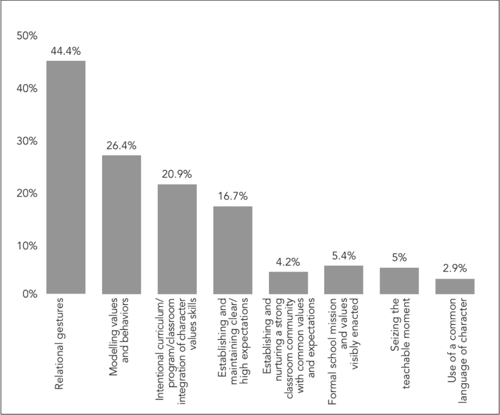

The following graph shows that the majority of character educators see the majority of their work being expressed through relational gestures – the heart of relationality in learning – and the way in which they model what they do to the boys. Around 20 percent of what they do is through intentional classroom activity – a percentage that corresponds by and large to what the boys see – while there is a smaller but still significant proportion of work done through the setting and maintaining of high standards.

Observable strengths and skills in character education: expert practitioner perspectives

Observable strengths and skills in character education: expert practitioner perspectives

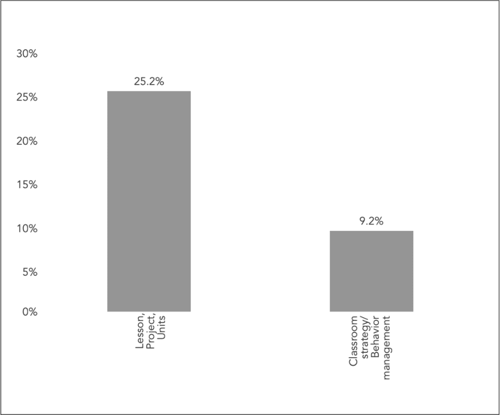

If we narrow our focus to responses related to the classroom, we can then fall into two sub-groups: narrations of lessons, projects or units of work, and those focused on classroom strategies and management procedures. This speaks to both specific curriculum content and also the way in which teachers relate to students. This is important because it shows reference to a blend of specific teaching content with approaches to the classroom that is, perhaps, not seen elsewhere. It also establishes clearly that expert character educators bring lessons on character into their classroom space – it is part of their core business, not something peripheral.

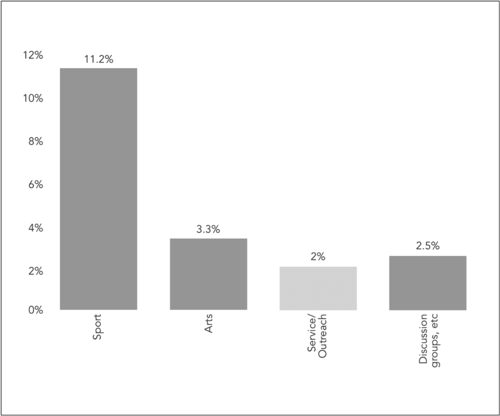

The category of co-curricular activities falls into four sub-groups: sport, arts, service/ outreach and discussion groups. What is perhaps most surprising and confronting here is that the area of service learning (shown in the lighter shade) is significantly under- represented. Given the dominant theme of service to others in boys’ schools that underpins many of the assumptions about character education in schools for boys, this figure leaves much room for improvement.

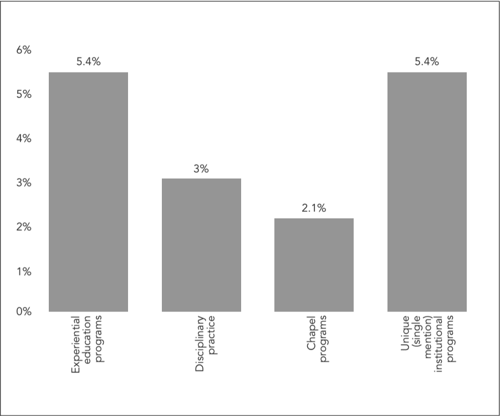

Best practices in institutional programs or events falls into four categories of experiential education programs, disciplinary practice, chapel programs and unique institutional programs. The highlighting of these four areas is not surprising since they feature heavily in the institutional pillars and brand characteristics of so many boys’ schools.

Best character education practice in institutional programs and events: expert practitioner perspectives

When it comes to the assessment of student character outcomes, the majority of teachers present a strong case for some form of assessment based on close observation over time of individual students, of classroom climate, and of overall school culture. Such observation may be supplemented with a variety of other strategies and tools: student writing, online surveys, notes from faculty meetings about student progress, and through monitoring a range of school statistics such as student involvement in the co-curricular program, and the number and kinds of disciplinary infractions. However, across all of the responses we have seen to questions on this topic, there is not much commentary at all about a common language for assessment or about the value (or not) of some form of rubric or reference system for understanding growth or achievement in character development. On the other hand, almost no one resists the premise that assessment of student character outcomes is both possible and desirable.

We have already talked of the way that fit for purpose schools of character develop a community of inquiry and practice that addresses the need for solutions that are both personalised to the needs of people, while simultaneously aligning these same people to organisational culture and goals. Such a community dares to ask the most important of questions and to seek answers for them that blend professional experience with the best research available: What are the characteristics of effective practice in character education? What conditions – personal, professional and organisational – support it or get in its way? What might teachers tell other teachers about what it takes to be good at character education? What approaches and strategies in character education seem to work especially well for students? Can character development be assessed? How might we design a professional community in character education that might lead to improvement?

Schools, therefore, need to think through how they might develop this capacity. This will require them to think about how best to shape the trajectory of their educational development strategically. Throughout the process, teachers need to be engaged in the formation and growth of such an evidence- based community of inquiry and practice. This is perhaps the one area that we have found is lacking in most schools, even those which might properly be termed ‘schools of character’.

In the absence of such communities of inquiry and practice, currently, we have found that overwhelmingly, the most significant factor in building expertise in character education is currently personal experience – learning about what works well by reflecting on one’s own practice, usually in relative isolation. This was followed by the impact of colleagues as role models or at least as case studies of how to be good (or bad) at this, and mainly by observation and osmosis rather than any formal professional dialogue. With considerably less frequency, professional development offered in or outside the school and prior professional experience (such as a previous job, career or education) were mentioned. Trailing behind these front-runners were: school ethos and mission, parenting experience, senior school leadership, mentors, the students themselves, faith/religion, the role of athletic and coaching, and experiences in positions of responsibility.

Professionalism in teaching has always been more than competence. Our conclusion is that in most schools, teachers are usually operating as solo practitioners as character educators. They report that they “grow” in their character work largely through individual reflection on their own practice as well as by the mostly informal inspiration and example of their professional peers. This is sometimes mediated by other school influences, and sometimes by more deliberate professional development, usually in support of specific initiatives or programs adopted by the school (e.g. positive psychology). Sometimes the influence of long-standing heads or principals, especially in smaller schools, is felt. Yet we also note that, even in schools very committed to character education, the impact of formal professional development or of leadership on actual practice is fairly low. This broadly aligns with findings from our character education surveys, and indeed with a larger research literature about the long-term inconsequence of certain types of professional development, such as “one off” speaker events. Survey statements about professional practice and the existence of some sort of community of practice in character education rated almost always as the lowest of all questions, as we have seen. Overall, growth in teacher learning in character education is largely driven by personal commitment and motivation, fuelled (we would suggest) by these same teachers’ sense of purpose and commitment, no doubt with the belief that they are in alignment with the core mission and vision of the school. Our work to date clearly illustrates the opportunity for schools to leverage this individual work through the creation of a strong community of inquiry and practice aligned individual effort with common agreement about shared direction, focus and language.

In addition, we have been able to develop a detailed portrait of this critical work that reflects its variety and complexity while providing some key common themes. The most immediately evident global conclusion is that all teachers who responded believe character education to be fundamental to their work – equal to, or sometimes even more important than their academic and co-curricular responsibilities. We sense that it is the foundation of all their work, and the foundation of all learning. Furthermore, they see the work as holistic, permeating all aspects of their work and interactions with students.

We have hypothesised elsewhere that the most memorable character education seems to flourish best when students are engaged and involved in a certain way. Again and again, we see variations of the cognitive apprenticeship model, so much so that we have declared a derivative or related character apprenticeship. Another characteristic of the students’ own community of inquiry and practice therefore focuses on the pedagogical approach that best accommodates this process of gaining expertise in character matters. In the last chapter, we proposed a ‘character apprenticeship’ teaching and learning model as especially salient. It seemed to illuminate what experienced teachers told us about their effective work in character education and narrated in many of their stories of memorable and representative practice. It would seem to resonate with the students’ reflections on the processes of their own character practice and reflection and might best capture their sense of self-agency and interaction within their community of inquiry and practice.

In its current state in schools, there is a hidden and tacit world of professional knowledge in character education that needs to be made explicit and made better for all in the process.

Expert teachers can articulate a clear philosophical basis underpinning their work as educators for character, even if the exercise is unusual and novel to be encouraged to give voice to this purpose, and certainly to share it. This philosophical purpose seems to animate and make of their approach to character education. It would, we think, be valuable for all teachers at critical points in their career cycle to create, reflect on and return to such a fundamental expression of their professional ethic and responsibility. While sometimes deeply personal, finding this purpose is not necessarily or only done in isolation – it could well and profitably be a shared professional exercise, a jumping off point for professional collaboration and development. A staff or faculty might then evolve a shared and common purpose as a starting point to developing a genuine community of inquiry and practice.

The teachers we have spoken with view their prime work as “character building” in a very specific sense. Work routines, high classroom standards and the “character of my classroom” – what students can expect to see and be asked to uphold as members of this class mesh together under the strong directing presence of the teacher, adjusting and responding to the flow of student engagement and attention, deftly drawing them into line and the class into focus. In many of these accounts, there is a conductor’s quality to their crafting and monitoring of the character of the learning environment itself. Here, the emphasis is on strategies that repair and strengthen the norms of the classroom as a community of learners, and put on display and reinforce those ‘character traits’ made manifest in the learning environment. All activities, as in the extra-curriculum and pastoral programs, are significant character-building learning environments, and should be crafted and led in the same way and for the same purpose.

We are led to the conclusion, in fact, that this body of pedagogical knowledge and this level of effectiveness in character education, while complex in so many ways, is identifiable and discussable – and certainly so if and when the right conditions and direction for professional discussion and growth are set in place. In its current state in schools, there is a hidden and tacit world of professional knowledge in character education that needs to be made explicit and made better for all in the process.

We can observe that expert teachers walk a perhaps imagined but also visible ‘character infused pathway’ in the course of their various responsibilities and in the light of their ‘presence’ in their school community. For these teachers, particular formal roles may be concrete and separate, but the moral or character foundation of their work is continuous and holistic and formal and informal. This notion of character infused pathways suggests, as we noted, that character education happens in multiple spaces, occasions and interactions across and throughout the school. Understanding this is foundational to the effectiveness in character education, and to the principles that might inform a community of inquiry and practice. This will require significant reshaping of the way in which our profession currently approaches its work in character education.

Elsewhere, we look at how the character development of students follows a path from ‘me’ to ‘you’ to ‘us’, as they adopt guiding questions that influence his development: “Who am I? Where do I fit in? How can I best serve others?” We have seen that it is when they reach this final question on their quest and focus on how best to effect solutions that address the needs of others that their fundamental purpose demonstrates an incipient and emerging adulthood. In other words, students become adults when they can show that what motivates them and engage them most in the world is not furthering their understanding of themselves and their relationship to their context, but rather their determination to act in a manner that attends to what others most need of them. Their individual selves and therefore their wellbeing are important still, for without it they cannot properly help others in a sustainable fashion. Nonetheless, what we learn from schools both implicitly and explicitly, is that the expectations of these institutions and their stakeholders is that good people care for and serve others.

How might students know about the ways in which their paths in character education, their process of realisation and replication, are progressing? It comes down to assessment and the formative feedback that lies at the heart of it. As we have observed, the great majority of character educators grasp the importance of trying to assess the effectiveness of their work on character, while clearly articulating how complex, nuanced and authentic any such tool would need to be. However, within most schools and for many other teachers, degrees of resistance and even sometimes an almost allergic reaction to this potential persist. A shared understanding of outcomes for students in character education and a common professional language for assessment and evaluation will need to be built before that constraint is dissolved. We would recommend the widespread development of an ‘assessment mindset’ in character education. This needs to be a key ingredient or dimension of an appropriate community of inquiry and practice focused resolutely on student learning and growth in the various domains of character education. There would need to be a professional conviction that character growth and development can be assessed; that valid and appropriate tools and methods can be developed to do so; and that this assessment can lead to feedback to students that is appropriate, authentic and beneficial to their character learning. This assessment and evaluation mindset would also extend to evaluation of programs related to character education, school climate and culture, and professional learning as well.

We know that teachers are able to identify, describe and evaluate specific practices for pedagogy, curriculum design and classroom management that they considered to be especially effective for student character growth. They see shaping the culture of their classroom – routines and norms of the everyday teaching environment – as impactful. At least collectively, they are also able to connect and see a common and adaptable approach across the full range of their responsibilities and presence in the school. Their practice should be, to use a phrase we explore elsewhere, ‘warrantable’.

"At the heart of this community of inquiry and practice, lies relationship."

At the heart of this community of inquiry and practice, lies relationship. Expert teachers most often refer to their relational connection to students as the richest pathway for their effectiveness as educators for character. They were able to describe how this relationship- building, while an end in itself, is the very medium through which to engage students in their character development. They stress the importance of this relational connectedness – deploying a range of deeds, words and gestures, role modelling positive character traits, and being and being seen as authentic – as especially powerful and impactful for students.

In a famous article on the relational quality of being a teacher, Rodgers and Raider-Roth quote Max Van Manen: “Pedagogy as a form of inquiry implies that one has a relational knowledge of children, that one ‘understands’ children and youths: how young people experience things, what they think about, how the look at the world, what they do, and, most importantly, how each child is a unique person. A teacher who does not understand the inner life of a child does not know who it is that he or she is teaching. Moreover, the concept of pedagogy not only refers to this special knowledge it also includes an animating ethos. A pedagogue is an educator (teacher, counsellor, administrator, etc.) who feels addressed by children, who understands children in a caring way, and who has a personal commitment and interest in children’s education and their growth toward mature adulthood.”

This relational connectedness certainly involves this animating ethos but it is not therefore vague and mysterious; these teachers see it as a practical competency to be developed and improved. In other words, good people are the product of relationships and themselves become experts in contributing to character apprenticeships. The communities of inquiry and practice that supports such relationships are the knowledge engines of schools of character.

In developing these communities of inquiry and practice, we need to apply the same principles of professionalism to character education practice that we do to other fields of education. Schools recognise the need to prepare their students to thrive in 21C and are willing to explore how notions of character and competency might assist them to do this better. Currently, they rarely construct focused, aligned and targeted approaches to character education that align vision, intention, means, execution, and evaluation to a specific set of desired character outcomes for their graduates. Simultaneously, while some professional learning occurs among educators in these schools, it tends to occur in isolation and without the support of an evidence-based and supportive community of inquiry and practice.